I

I didn’t want to pray. I didn’t want to read the Qur’an. And I didn’t want to fast. Performances required of me daily, annually. To not eat, to move my eyes over Arabic letters, to stand up, bend down, prostrate, get up, sit on my knees, thank God. I didn’t believe it mattered. I didn’t believe in Allah. And I didn’t want to cover my hair for a supposedly benevolent, magnificent being, or read the words that being delivered, via Angel Gabriel, to the illiterate Prophet Mohammed, the most unlikely of chosen ones. But I moved my body as required, wrapped my Qur’an in silk scarves, and put my breakfast down when the sun came up. Life was a charade, orchestrated to please authority. Prayer rugs were shifted, the Qur’an opened and closed, the wazu vase filled and emptied to look like water had poured from its spout. Water wiped across my forehead with my fingers, just enough to dampen my bangs, to make it look like I’d completed my ablutions. Signs. Symbols. A theatrical production staged to keep the peace.

Islam, for me, was a distorted, two-culture family drama, in which my parents played an unspoken game of high-stakes chess with one another, enacted in small moves, one square at a time, trying to gain territory, to win over, influence, control the kids, steer them toward or away from Allah. One was honest with his plans, hiding nothing. He said, This is what I want. The other was surreptitious, deploying spies, planning a coup, rearranging her pawns when he looked away. Religion is complicated. And when a religion is under attack like Islam, when Muslims’ lives are devalued and individual acts of violence indict millions, when women who cover their hair are threatened and persecuted because females everywhere must let everyone see their black yellow brown white hair, or else they are terrorists or not free, I wonder if this is the moment I should tell my story.

My childhood religious instruction went sort of like this:

On the Matter of Chadars (BTW This Is Not a Misspelling: Chadar Reflects the Afghan Persian [Dari] Pronunciation of چادر, the Pronunciation I Grew Up with, Said chaw-Der, which Almost Rhymes with my Last Name, naw-Dir, If Said Correctly, With a Fluttery, Rolling-R Emphasis on the Last Syllable, as Opposed to the Iranian Persian [Farsi] Pronunciation Chador)

Father: We’re going to the mosque. Where’s your chadar?

Mother: Headscarves are stupid.

Father: Fix your chadar. I can see your hair. How many times do I have to tell you?

Mother: Why do women wear headscarves? And why not men? How come men’s hair doesn’t have to be hidden?

Father: Women wear chadars to protect themselves.

Mother: Oh, so men can’t control themselves around women’s bodies, they are total maniacs, and women have to hide behind fabric so they don’t get hurt? Look around America. I don’t see a bunch of men attacking women because their hair is showing, do you?

I need to clarify: this back-and-forth dramatic reproduction does not refer to any real conversation held between my Afghan, Muslim father and my Slovak-American, latent Catholic mother. My parents did not deliver these statements in the spirit of debate or how-should-we-raise-the-kids discussion. Their pro- or anti- Islam stances were not even uttered in each other’s presence, at least not exactly or directly. My father delivered his pronouncements to his children, in the “public” space of the home, which, for a patriarch, is wherever, whenever. No need for self-censorship. His law, his rule. Sometimes relayed gently, Come here, let me explain. Sometimes dropped down from above in the form of wall-shaking commands that made his children scramble and pretend they had something to do in another room. So, although he wasn’t addressing my mother, she heard all.

My mother expressed her opinions privately, when my father wasn’t around. After hours, so to speak. She was a teacher at the same school attended by my siblings and me, so our schedules were coordinated, our movements aligned. Plenty of Mom-kid time while my father was at work. When we returned home in the afternoon, at the end of our school day, my mother chipped away at my father’s faith while warming dinner at the stove, letting me and my siblings catch up on all the TV shows he didn’t allow. (When I was a teenager, she secretly recorded Saturday Night Live for me with the VCR—from our tiny New York State living room, NYC was already calling me.) In the dark early evenings of winter, when the sun would set at 4:30 pm, she casually questioned the oddities of Afghan culture while handing us ornaments to hang on our plastic Christmas tree before he got home to object. (Once it was laden with crude ceramic ornaments made by his children stabbing away at clay in art class, how could he order the tree taken down?) While my father was pressing his foot to the gas pedal, changing lanes on Rochester’s 490, cruising down 441, headed home to a split-level ranch in rural Wayne County, his family was living a life he couldn’t imagine. His home in the country was full of Americans who loved Christmas and un-Islamic TV. It was full of Americans who shifted to our own special version of Afghan theater the moment he opened the front door.

Salaam Baba jaan! Yes, we said our prayers, yes, we read a page of the Qur’an, yes, yes. Let’s eat dinner, Bismallah-i-rahman-i-rahim.

And he smiled, so pleased. He was proud. He didn’t know.

My father was consistent. Or maybe I should say he was transparent. Not because he tried to be but because he couldn’t help it. His needs, loves, fears, paranoia, he flung them around the house—the way a toddler clenches his fists and screams because he doesn’t have the skills to be more diplomatic. The world was good/bad, moral/immoral, black/white. Afghan/not. Emotions, hopelessly, painfully bare. (Do you love me?) And my mother was a puddle of distracted grey. I looked in her eyes, I tried all the time to initiate a meeting, a spontaneous one-on-one, Hey, it’s me, but they always bounced unavailable. My mother lived one way in my father’s presence, another when he wasn’t around. Please the patriarch, roll your eyes behind his back. Lessons for her children on how to live a double life, never addressing what was really going on. It was like grade school: she and I had a nasty clique, spreading rumors, picking on the weak kid, playing nice when an adult—the principal, the lunch lady—walked by. My father was the weak one and he was the authority.

About Sunday School, which Most Local Muslims Believed Should Really Have Been Saturday School, Because Sunday School Sounded Too Christian, But the Mosque Leadership, in the 1980s, Decided, Despite Fervent Disgruntlement, Better to Align the Calendar of the Islamic Center Of Rochester (“I.C.R.” for Short) with Regular American School Schedules, so Extra-Curricularly Inclined Muslim Kids Could Compete on Saturdays with their American Classmates in Soccer Games, Wrestling Matches, Science Fairs, Chess Tournaments, and Spelling Bees (This Policy Has Since Changed)

Baba: Dr. Malik says the new mosque in Rochester is ready to open.

Mom: Religion. Everyone getting together to worship a god they can’t see. Have you ever seen this Allah? Where’s the evidence?

Baba: No more meeting in the basement at Dr. Malik’s house. What a wonderful day. Rochester opens its first mosque!

Mom: Dr. Malik—he seems like an arrogant man. Where’s his wife? What does she do? Have you ever seen her when you were at his house studying the Qur’an?

Baba: And the mosque has started Sunday School classes!

Mom: My parents made me go to Catholic School on weekends. The nuns liked to hit kids with rulers. Right here, on my knuckles, like this.

Baba: I signed you up for Mrs. Bakari’s class for 11-13 year olds.

Mom: Who is Mrs. Bakari? All the mosque teachers are Pakistani housewives with no education, bored women looking for something to do. I wouldn’t trust them to teach children.

Baba: I’m disappointed you got a 60% on your test on the life of Prophet Mohammed. This is a very serious topic. Prophet Mohammed, peace be upon him, led a life that is a model for all Muslims.

Mom: Don’t worry about that quiz. You read a long book, poorly written, with spelling mistakes, and she quizzed you on three random facts hidden in two paragraphs. That’s not how you make a test.

Baba: And Mrs. Bakari tells me you haven’t been memorizing your surahs.

Mom: Memorization is not how kids learn, memorizing chapters word for word that they can’t even understand. What do you even get out of that? Do you even know what any of it means? Maybe Mrs. Bakari should teach you Arabic before she requires you to memorize a bunch of Qur’an chapters.

The mosque’s special school and Sunday prayers colonized half our weekend, which was a real tax on my schedule. By the time I was a teenager, I didn’t care about being a good Muslim, praying, memorizing, chadar-ing, and all that. I was a Huge Nerd, and by high school, I was obsessed with “getting into a good college.” I’d rather have been reading, and re-reading, a chapter of white-washed American history from a state-sanctioned textbook all weekend than praying at the mosque. I had a plan, and it took time: perfect grades → win a full-ride scholarship to a college faraway → escape my parents’ house → achieve independence. But attending Shouldn’t-Be-Sunday School was non-negotiable. I didn’t even feel I could fake sick. Plus the future of Afghanistan depended on my family.

My father was sort of the leader of the local Afghan community at the time. He was the most assimilated, the most American, the one with the American wife and the four Honor Roll children, the one who’d actually chosen to go to college in the U.S., and to move here permanently, before the war with the Soviets had even broken out. But he was also extremely patriotic. When the Cold War, and the Russian tanks and the American rocket launchers, denied him the option to return home, he became obsessed with saving Afghanistan, its people, its culture. He sponsored refugees and helped them adapt to American life. He wrote our congresswoman about expediting immigration applications for not only family members but also total strangers. He wrote his senators. He called newspapers and news stations and gave interviews. He provided his perspective on “Escaping the War in Afghanistan,” which was the title of an article in Rochester’s Democrat & Chronicle, and I’ve even found a quotation from him in the Los Angeles Times, about the Soviet withdrawal of troops in 1989. Locally, he took it upon himself to ensure that all area Afghan kids didn’t “lose their culture.”

Every Sunday morning, my father drove into Rochester with his four children and gathered up all the Afghan youth he could find to deliver to the mosque’s Shouldn’t-Be-Sunday School. We picked up confused Afghan refugee kids who spoke no English and lived in furniture-less apartments with their parents in crime-ridden inner-city neighborhoods. We picked up the snazzily dressed offspring of Western-educated Afghan bourgeoisie who resided in sterile housing-development cul-de-sacs. When some Egyptians at the mosque realized my father was driving around town, acting as a self-appointed Mosque Busdriver, willingly picking up any young Muslims he could fit into his van, we started picking up their kids too. Our services targeted spiritually imperiled Afghan boys and girls, but ultimately, we made no distinctions regarding class, color, ethnicity, nationality, or dialect. No matter if there weren’t enough seats to go around, no matter if we had long ago run out of seatbelts. Equal opportunity pile-up. If you were Muslim, climb aboard my father’s Volkswagen van. I called it the Afghan Cara-van.

On our way out of the house into the caravan on Sunday mornings, my siblings and I marched down the stairs with our backpacks filled with Qur’ans for memorizing surahs and typed-up, photocopied reading assignments¹. I already had wrapped my chadar around my brown, Slovak-Afghan hair, and I watched my little brother leap down the steps, his head of curls bouncing like an advertisement for body-building miracle shampoo. I fantasized about shaving my head. Would that be modest enough for my father? If my hair was so controversial, why not lose it altogether? Why did I have to keep my hair long and then wear a scarf over it? Wasn’t that a circuitous route to modesty? And why, on Sundays, did my father make me put it on before I was even out the door, as if the mosque grounds, and Allah’s gaze, suddenly extended into our front yard on Sundays, which, of course, was the Christian holy day?

…

1

I avoided memorizing surahs, but I loved reading those little booklets. They came in the form of photocopies of photocopies, authors unknown, publishers long gone, stapled and bound at copy shops and sold for $5 a bundle in the mosque’s library-store. These were our only English access to Islamic history, to the details of the life of Prophet Mohammed, to the cities of Mecca and Medina circa 600 A.D. Full of folklore and legends and narrative designed for kids, these stapled booklets never got around to declaring moral rules, except for No Killing Spiders, because a spider once saved Prophet Mohammed’s life, and I’ve never killed one (purposefully) since.

You can read the rest of “Bad Muslim” by Leila Nadir in Aster(ix)’s Fall 2018 print issue, Edges, available for purchase wherever books are sold.

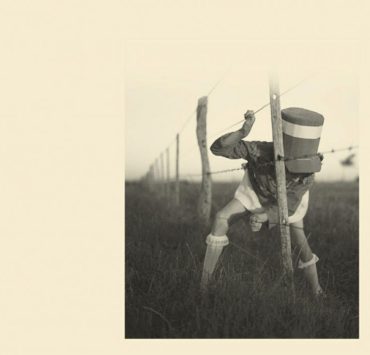

Image Credits: TAHA KREWI, 2013 "Reading Qur'an"

Leila Christine Nadir is an Afghan-American artist, writer, and educator. She is the author of award-winning essays and artworks about public health, the Afghan diaspora, environmental theory, and her personal experiences of religion, ethnicity, trauma, and healing. Her primary project right now is her childhood memoir, titled Bad Muslim, which chronicles growing up within the colorful, turbulent marriage of her Afghan, Muslim father and Slovak-American, Catholic mother, who together raised seven children. Excerpts have appeared in Aster(ix), North American Review, Asian American Review, and McSweeney’s Internet Quarterly. She earned her PhD in literature from Columbia University, and is currently an Assistant Professor at University of Rochester, where she is also Founding Director of the Environmental Humanities Program. More info about her work can be found at http://leilanadir.xyz/.