Run. Being run. Run on asphalt. Being run on asphalt with old sneakers. Being run on asphalt with old sneakers and no direction. Being run on asphalt with old sneakers and no direction only so much as away. Being run on asphalt with old sneakers and no direction only so much a way as forward.

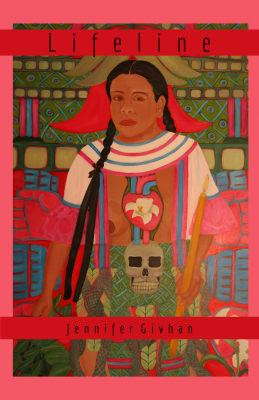

I begin by noting running, and the aesthetic of running, to enter this chapbook. The poems in this work conjoin for an inventiveness of spirit. Givhan’s poetry here manages to keep my mind and body in motion. As a counterpart, I think of the crushing stillness in Paul Celan’s work as the perpendicular poetry, intersecting with Givhan’s vital language at the concept of form. The forms that Lifeline works through are wide: some have a more traditional look to them; more often, though, these poems are delighting in lineation, white spaces, and alignments trying to challenge the form of the poem to craft just as much of an image as the environments where the poem, inescapably, finds itself.

Whether or not the formal modes explored within Lifeline are always evocative for me or if I sense a tension in connecting the form to the poem, the dexterity with which Lifeline is arranged keeps me actively thinking and engaged throughout. I want to know the prickliness of the cacti described versus the prickliness of the white spaces. In “Girl with Death Mask,” the poem is splayed across two pages. Surrounded by boxed-in notations, continuations, or expansions of the poem, the center lines contend with life voraciously,

“ I wore a watermelon pink dress

tied at the back when I was a girl

& never imagined the funerals

I’d become.”

The poem is after Frida Kahlo—chasing after and in dedication of—is a poem that strives to address something immense and uncontrollable, and so the form has to become more to match the poem’s ambition.

The landscapes that bloom throughout Jennifer Givhan’s poems are full with life in its bare essences; sometimes dangerous, sometimes tender, the world has a way of giving shape to the conflicts one has both daily and eternally. The landscapes make me ask: What violence are you willing to put up with for the sake of convincing yourself you are in love?

At its strongest, Lifeline is ripe with poems whose lines resist explanation. The poems within set the reader up for an explorative quest for which the reward is a genuine look at understanding the interstices between scenario, voice, and image. I think of lines like in “Snakes-Her-Skirt,” such as: “and I can’t bear myself / asking for something as mundane // as death.” On an individual basis, the lines are striking and confessional (“I can’t bear myself”) and pay careful attention to the central poetic formation of death.

The attention of this chapbook is playful and serious. Lifeline is unafraid of the voice that necessitates white space. This voice engages with confusion and makes the reader want to throw a party with it, celebrate and have a conversation that can go from talking about a summer job to the last letter they wrote. The white space makes the reader want to explore what the line before contains, what the moment means, and like any good poem, it demands an attention to the process. I think of Givhan’s poem, “Curanderisma,” which has a clear center divide with white space, as if the separated stanzas are being asked to call out and respond to each other. The speaker’s voice here transforms from the observer, the describer, the attempter, to the engager and the participator.

Lifeline proves itself a powerful journey of a chapbook. It rewards with introspections on sexuality, violence, relationships, and belonging to a world in which things seem futile and hopeful, struggling and empowered. But further than that, Givhan’s voice guides me toward, into, and through trouble in as imaginative a way as I have seen.

Buy the book.

Jennifer Givhan (Lifeline) is a Mexican-American poet from the Southwestern desert. She is the author of the full-length collections, Landscape with Headless Mama, which won the 2015 Pleiades Editors’ Prize, and Protection Spell, winner of U. of Arkansas Press’s 2016 Miller Williams Series Prize, and two poetry chapbooks, Curanderisma (Dancing Girl Press, forthcoming 2016) and The Daughter’s Curse (ELJ, forthcoming 2017). Her honors include an NEA Fellowship, a PEN/Rosenthal Emerging Voices Fellowship, The Frost Place Latin@ Scholarship, The 2015 Lascaux Review Poetry Prize, The Pinch Poetry Prize, and her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Best of the Net 2015, Best New Poets 2013, AGNI, TriQuarterly, Crazyhorse, Blackbird, The Kenyon Review, Rattle, Prairie Schooner, Indiana Review, and Southern Humanities Review (where she was a finalist for the 2015 Auburn Witness Prize). She is Poetry Editor at Tinderbox Poetry Journal and teaches online workshops at The Poetry Barn.

Cody Stetzel is a poet from Upstate New York. He spent two years suffering in the heatstroke wasteland of northern California and all he received was an MA in Creative Writing from the University of California at Davis. He has since been a staff reviewer for Glass Poetry Press. Now he's in the pacific northwest because there's no better way to embrace struggle than to sit outside in the rain. He sincerely hopes you're having a good day. Previous publications can be found in Neovox and the East Coast Literary Review.