I met Violeta when I was twenty, on my first trip back to El Salvador in 2002. I flew overnight from San Francisco to Comalapa and spent the whole trip staring out the window into the darkness, waiting to catch a glimpse of the country of my birth, a country I hadn’t seen since infancy. The professors that I work for had connected me with an organization, the Memory Seekers, Los Buscadores de la Memoria. Our department had just begun partnering with them to process DNA collected from adoptees like me, and from the families whose children disappeared during the civil war. Though at the time I was unaware, the department had already tapped me to be their adoptee ambassador, their mascot.

A few hours in, we hit turbulence, and the plane trembled and dropped altitude, a split second of free-fall. The cabin filled with whispers, the woman beside me made the sign of the cross, and I curled my knees into my chest and held myself tightly. I remembered anxiously that one of the professor’s had said TACA, the airline I had booked, was known as the Take-A-Coffin Along airline. There had been a crash or two, but not to worry, he’d ridden on TACA plenty of times. He’d said it as though this would impress me or impress upon me that he’d been brave enough to leave the comforts of the first world and fly headfirst into danger.

When I told my mothers what he’d said, the color left their faces. Stevie laughed it off and told yet another story about backpacking through London when she’d been my age. Denise tucked photocopies of my passport into every piece of clothing I packed, like that magic paper was an amulet against death. But I wasn’t afraid of injury or traveling alone. I feared arriving to a home that I’d forgotten or, worse, had forgotten me.

Just as we began our descent, the sun rose. I’d never seen a place brimming with so much green. The plane glided past a beach and turned around over the ocean to land smoothly on the runway. Immediately when I exited the plane, I noticed the density of the air: it felt heavier, the heat prickled. My senses were wide awake, even after a sleepless night. I wanted to pour every detail into my memory. At customs, the agent spoke to me in Spanish, evidence that I blended in. I tried not to let his confused look, when I answered him haltingly, disturb this illusion.

My grandmother’s housekeeper, Ameríca, had arranged for her brother to pick me up from the airport. He was standing outside the baggage claim with my name, Nina Miller, on a sign. I was disappointed he looked nothing like Ameríca––that breach in genetic inheritance. She hadn’t seen her brother in over ten years, he was just a teenager when she’d left El Salvador, and she’d sent me with an enormous suitcase so full of gifts, it had to be bungee corded shut to make sure the zipper didn’t burst. I presented it to him, and he gave me a goofy, delighted smile in return. I liked him immediately. He drove me to a hotel in San Salvador, the same hotel my parents stayed at when they’d adopted me nineteen years earlier.

Along the way, the brother would point and say words I would repeat back as if I had understood him. I tried to hold the words in my mind, but the letters and sounds vaporized as soon as they left my mouth. Along the road, an explosion of plants: ancient looking trees and overgrown bushes, hairy vines slithering through barbed wire fences. Vendors in brightly colored, ruffled aprons sold golden coconuts the size of bowling balls. Behind them, the shells were piled up, cut open and burning. The dense smoke curled into the car’s open window.

“Aqui, creo,” he said, as he turned up a manicured drive. The hotel towered over the surrounding buildings, with imposing arches and decorative roman columns. He let out a low whistle as he pulled up to the curb. I copied him, pretending to be overwhelmed with the luxury, as though I’d never seen anything so grand. The heat of embarrassment rushed through me. I prepared myself for the brother’s generous smile to twist into a sneer, a “must-be-nice” look on his face, his analysis of my privilege, his recognition that I was a “fake.” But the brother nodded his head with approval at the gleaming white walls. He helped me out and squeezed my hand between his, as though I was dear to him.

“Wait!” I remembered the disposable camera I’d packed. I found it in my backpack and snapped a photo. “For Ameríca,” I said.

When I got to my room, I called my mothers to let them know that I’d made it. Stevie answered, “How’s the hotel?”

“Fancy.” I said. “I’m in room 907. Do you remember what room you were in?”

“What room were we in, Denise? Do you remember?”

I heard Denise’s soft voice in the distance, “Second or third floor. It had a balcony that looked out over the pool.”

I looked out my window, I was facing the front side of the building. The volcano of San Salvador towered over the skyline. “I haven’t seen the pool.”

“It’s a nice pool,” Stevie said. “Did you bring your bathing suit?”

“We saw a bomb go off from the balcony,” Denise said. “The last night we were there.”

“How close?” I asked.

“Too close.” Stevie said.

* * *

The next morning, the Memory Seekers, Yenni and Chepe, came to get me. At the time, the two of them were the whole organization. Together they combed every corner of the country, connecting the families of the disappeared. Yenni was my age, but she seemed older. Her sparkly nail polish and the bright artisan cloth bag slung over her shoulder were so cheerful in comparison to the serious look on her face.

“Ready?” she asked, English sounded round and warm when she spoke it. She extended her hand to me. Her arms were covered in long, silky black hairs, but the hair on her head was short and frizzy. Awkwardly, I reached to shake her hand, but she laughed, took my hand in hers and walked me to the truck outside. “We are going to Nueva Esperanza.” The town had many unsolved cases of missing children, and the organization was holding a Day of Memory there.

Chepe opened the truck gate. “You ride back here. It’s more fun.”

“How long is the ride?” I asked casually, throwing my bag onto the truck bed.

“One or two hours,” Chepe said.

“Great.” I climbed in beside the file boxes and DNA kits. I put my bag under my head and looked up at the morning sky, imagining my body parts scattered along a two hour stretch of road. I’d only ridden in the back of Denise’s truck the few miles back and forth from the beach, packed tightly between the boogie boards and the beer cooler. The truck set off and the wind streamed around me. When my initial fear of annihilation was overwhelmed by a curiosity to see where I was, I sat up and saw many other people riding in the backs of trucks. I smiled and waved at them, and they looked at me wondering what my problem was. Chepe laughed at me as he knocked the glass and gave me a thumbs up.

Violeta greeted us as we pulled up to the town square; a lone woman with a hulking frame bossing a push-broom over the concrete. As soon as Chepe and Yenni were out of the truck, Violeta strided over, patting her small pink hands on their backs. She had baby cheeks that glowed with the sun, and small penetrating eyes. She wanted to know who I was. As Yenni explained, Violeta’s eyebrows raised in curiosity. She stared straight at me, so intensely I became conscious of my own breath. She asked my age.

“Twenty,” Yenni replied for me.

She pulled me under her arm and held my head against her shoulder. My body was swallowed by the largeness of her body, constricted in the muscularity of her grasp. Her hand quivered as she held me. She said something in Spanish. I looked over at Yenni for help.

“Violeta has a missing sister the same age as you. She says, whoever your family is, they haven’t forgotten you.” A dark flower bloomed in my chest as the sorrow in her embrace entered me. Though I’d considered it before, I sensed in my own body for the first time the quivering, terrible possibility that I had been disappeared.

People filled the town’s square, standing with their arms crossed, speaking quietly. Chepe ran an extension cord from the internet cafe, past the sleeping dogs, to the little patch of shade beneath an illegible faded banner. I learned later that it had once read Bienvenido a Nueva Esperanza, and had been gifted to the town by a Swedish Delegation ten years earlier, after the Peace Accords were signed in ’92. Yenni set up a table and a few chairs and I sat close beside her, so that she could translate for me. Chepe greeted the crowd. He told a story about a group of children who were stolen by soldiers during a military raid and left at an orphanage in the capital. The children grew up believing they were orphans.

“I was one of those children,” Chepe said. “The first few years after the war ended, dozens of children were reunited with their families. It was as though those missing kids had only been waiting for someone to call out their names, so that they could raise up their arms and be found.” He cleared his throat. “Last year, we celebrated the reunion of one lost child to his father in Morazan.” The crowd nodded, knowingly. “This year we have made contact with four new children, adopted abroad. We have one with us today.”

All the faces in the crowd turned toward me. I suddenly felt afraid, cracked open, like something primal oozed out of me. I’d suffered from anxiety as a child, and I felt myself sinking into that low pressure vacuum, visibly cringing, my palms dampening, my fingers turning to claws.

Some of the people in the square formed a line, maybe a dozen. Each person took a turn at the microphone, speaking the names of their missing: Enrique, Gladys, Julian. “The last time I saw my son, he was still afraid of the dark,” a man said. Yenni translated this to me in a whisper. Violeta took her turn, her husky voice boomed through the air. “My sister Isabela disappeared. My father was carrying her in his arms. My mother found my father dead, but his arms were empty. My mother still waits for her, twenty years later. Every day she asks, where is my daughter? Where is my Isabela?”

I leaned towards Yenni and asked her, “Their DNA is in your database, right?”

She nodded. I hadn’t matched anyone in their DNA Database. None of these people were looking for me. I let out a sigh of relief.

A few women walked past and stared at me. One smiled, one reached out and touched my head as though I were a sacred object.

I’d spent years tending my own wounds, the scars that formed around the edge of the unknown. I thought they were mine alone, but all these strangers shared them, too.

Yenni saw me wincing. “You give them hope,” she said. Their sort of hope was no bright beacon of light, it flickered like a candle burned to the end of its wick. Their hope was full of shadow. At that time, I had just begun my search for the answer to who my birth family was, the potential overwhelmed me. These people had been searching for too long.

Violeta came and stood beside me with one hand on my shoulder and shooed away the people coming behind her like she’d claimed me. It was weirdly comforting. I felt the edges of myself tuck in so that I’d fit into whoever it was she thought she’d claimed.

When the people had finished speaking aloud the names of the disappeared, the mood shifted, blowing away like a cloud. They’d summoned the ghosts from the darkness but sent them up into the sunlight. They smiled, mingled in groups, teenagers stopped on their motorbikes to look on. Violeta invited me back to her house. Yenni told me I should go, she and Chepe had a few hours of meetings with people around town.

“She knows I don’t speak Spanish, right?”

“That won’t stop her,” Yenni winked.

Violeta linked arms with me. We charged across the two-lane highway between the buses hurtling by, we passed the radio station, and then turned up a wide, dirt road. The hills were yellow with sun burned grass, and the sky looked oversaturated, a fluorescent blue. Men on horseback clacked by in tooled leather boots and stiff straw hats, their button-down shirts were mostly open exposing their muscled chests. I’d never seen men like that, looking like real- life cowboys. Violeta laughed, “Campesinos, bien bravos.”

She pointed to a house, and I caught the soft wood of the swinging gate in my hands as we passed through. The house had several rooms that all opened onto a covered patio. A girl ran to Violeta’s side. “Ella es mía,” Violeta pointed to herself and smiled. Her daughter was twelve then, with long curls gelled in tight ringlets down her back. “Elena,” Violeta introduced us. I held out my hand and the girl slunk against her mother, eyes to the ground, a shy smile on her lips.

I followed Violeta into one of the rooms, dark as a cave, except for a sliver of light coming through an open shutter. As my eyes adjusted, I saw a woman asleep in a hammock. Violeta leaned over her, “Mi dulcita.” She pulled her mother’s hands to her lips and kissed them. Violeta spoke to her mother like she was talking to a tiny child. The woman seemed immobile, her face complicated by deep wrinkles, and sunken eyes sealed tight, her lashes like stitches. I wondered how she was even alive. Her eyes fluttered, she moved her arms as if to sit up. She wanted to touch me, she reached out a hand and I hesitantly stepped nearer. Though her eyes were closed, or nearly closed, she looked at me with her face, sensing me as a newborn kitten would, head shifting ever so slightly. When my hand was in her grasp, she held it weakly. “Isabela,” she said quietly. The name filled the dark corners of the room.

“No, Mama,” Violeta said and kissed her again. “Hoy, no.” Not today. I wasn’t her daughter, but there was no one in the world I’d rather have been than Isabela. I felt myself become her, in that room, held in that fragile hand, the hand of a mother, the hand of my mother. The longing on the woman’s face was so misshapen, so terrible. It was like looking into a mirror, my face inverted, the shape of what was missing, not what was there.

“I’m Nina,” I offered. I could have been her daughter. I could have been Violeta’s sister. What a shame that I was not.

Violeta went to the wardrobe and pulled out a photo album. She shepherded me back into the sunlight and sat me at the table on the patio––the outdoors violently bright by comparison to the little room. She flipped through the pages, describing each photo in details that I understood nothing of. As she talked, I stared off into the dirt yard which had been meticulously raked like a bonsai garden, full of skinny trees bursting with the most beautiful, flirtatious, shameless purple hibiscus flowers. Chickens strutted around the yard, their proud breasts armored in feathers of the most intricate lacework patterns. She skipped through a few pages and found a photo of herself which she pulled from the plastic sleeve and held out to me proudly. She was seventeen in the photo, the year was 1988, she stood in a forest, wearing a green shirt and a red bandana, her curly hair swept up in the wind, and a lunk of a rifle in her arms.

Yenni and Chepe and I drove back to the city late that afternoon. Violeta had not wanted me to go. She’d shown me a nearly empty room in her house that could be mine if I’d just stay, just a night, but all week if I wanted.

“Hotel,” I’d said, and made what I’d hoped was a universal sign for sleeping, hands folded together under my head, eyes closed. The entire afternoon had been an extended pantomime, Violeta and her daughter trying to decipher the interpretive dance of my communication, laughing at my pronunciations. “Hotel, no,” Violeta said, and dismissed the idea with her hand.

When Yenni and Chepe finally drove up in the truck to get me, Violeta was sweeping the rafters of the room to get it ready for me, “muchas arañas” she’d laughed, and that I had understood. Just the mention of spiders made a scream start to expand inside my lungs. Yenni convinced Violeta that I had to go with them. I promised to return. I touched the arm of the old woman in her hammock and told her I’d see her again, though I never did. When I said goodbye to Violeta, she told me that we were sisters now. I assumed it was just a nice thing to say––everyone had been so welcoming to me, everyone had taken me into their hands, kept me close––but, I believed her.

* * *

On my last night in El Salvador, I went with Yenni to meet some of her friends at a bar near the office. I’d spent the two weeks taking Spanish classes and sight-seeing. I’d visited El Monumento a la Memoria y la Verdad, in Parque Cuscatlán, with twenty-five thousand names of the dead and disappeared etched into a stone wall, and teenagers making out in the grass beside it. But I’d spent most of my time in the Memory Seekers office scanning boxes of handwritten notes, photos, and all sorts of documents into a computer file, starting what would become my life’s work, this database of half-memory, half-hope.

We found a table in a muraled courtyard. The crowd was mostly young people drinking beers, acting like poets. Yenni ordered food for us, fried Yucca, pupusas, and sweet beans rolled up in plantains. “Don’t eat the curtido,” she told me, “It will make your stomach––” she waved her hands in a circle around her belly and made a face. My gringa stomach, she meant. I resented her for that, to be made to feel like an outsider who couldn’t handle a microbe. I reached a fork into the bowl of curtido, fermented cabbage, and took a bite. Yenni raised her eyebrows and laughed nervously. It was delicious.

“Brave,” she said to her friends, a girl from Barcelona, and a student from University of San Salvador with an acoustic guitar across his lap and a black beret on his head. The Spaniard had a topiary of hair radiating from her underarms, and an oversized lip ring that gave her an extraordinary pout. They spoke in Spanish, occasionally glancing over at me, but I understood little and made no effort to.

A boy came and sat beside me. He had curly black hair that hung around his face and was more attractive than the boys that usually might sit beside me. He lived in Canada, but his family was from La Libertad, near the coast; they’d left El Salvador during the war. He was there for the first time in his life, taking in the motherland, he called it. We drank for hours, and the night air turned crisp. He fished a sweater out of his backpack, which emerged crumpled, like a piece of rotting fruit, and offered it to me. I wouldn’t have, but I was cold, so I stretched the sweater over my legs. He pointed to my scars. They wrapped around my knee, crawled over my thigh, scars that had marked me before my memory began. For years I tried to get rid of the scars, with honey and baking soda, with lemon juice, onion juice, coconut oil. The scars remained, glistening, satin-smooth, hideous, but mine.

“What happened?” he asked softly. I hated that question, one more question I had no answer to. But the beer had made me as liquid as honey.

I smiled at him and said, “The war.” My voice was electrified by the mystery of that dark word, war. Violeta had been there. I’d been there, too. He nodded with a quiet knowing, but what did either of us know? We, two children of this motherland, lost to a war we knew nothing about, but home at last.

***

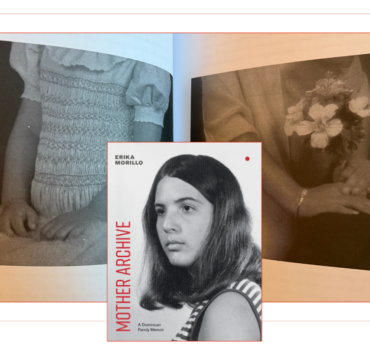

Image credit to Hilma Af Klint Foundation via OAI

Frankie Ochoa's short stories have appeared in La Presa, Nat. Brut, Kweli Journal, The Account, and elsewhere. Her short story "Still Life" received a notable mention in the 2018 Pushcart Prize Anthology, and is anthologized in Aster(ix) 10th Anniversary Issue (Blue Sketch Press). She is currently working on her debut novel, Citizen of Memory.