When self-imposed, constraints can inspire creative skill and innovation. Lauren Groff wrote a draft of her novel, The Vaster Wilds, in iambic pentameter. Picasso painted in blue for three years. Poetic structures like the sonnet or haiku invite writers to make connections they may not have otherwise. Then, there are the constraints we carry as we move through life—anxiety, trauma, self-judgment—that can weigh down creativity but become interesting topics themselves. There are the constraints—class, gender, race, religion, to name a few—that society imposes that stifle more than burnish creative expression.

Lately, I have been thinking a lot about my societal constraints. The rise of anti-Asian sentiment during the COVID-19 pandemic combined with the backtracking of policy and political attitudes around queer people have been deeply demoralizing. How tiring it is to watch politicians make up lies to win political support. How exhausting it is hear reports, again and again, of violence against Asian elders. How limiting it feels for people to reduce each other to something smaller than the humanity we all have.

How does one play with restrictions and limits—however they are imposed—to say something fresh and urgent, much less find joy?

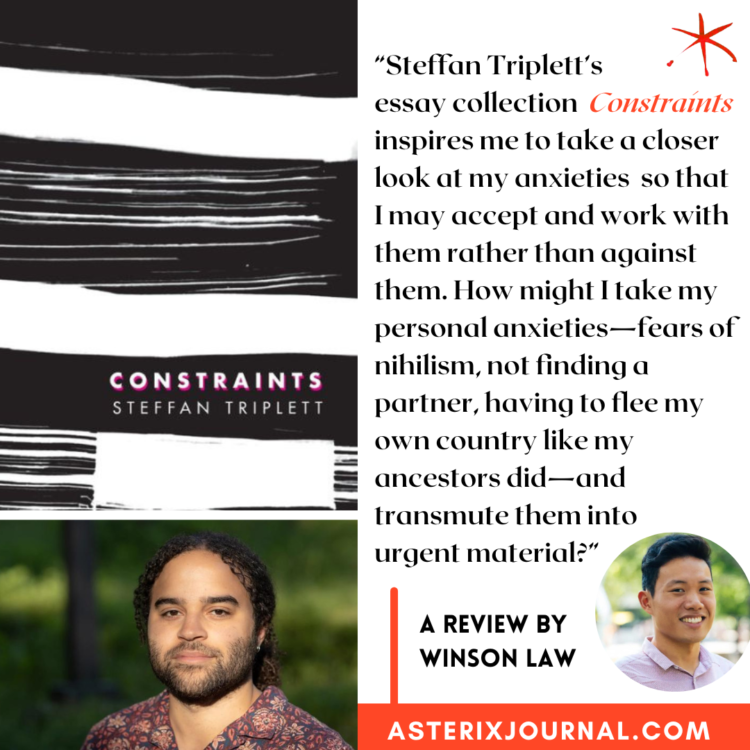

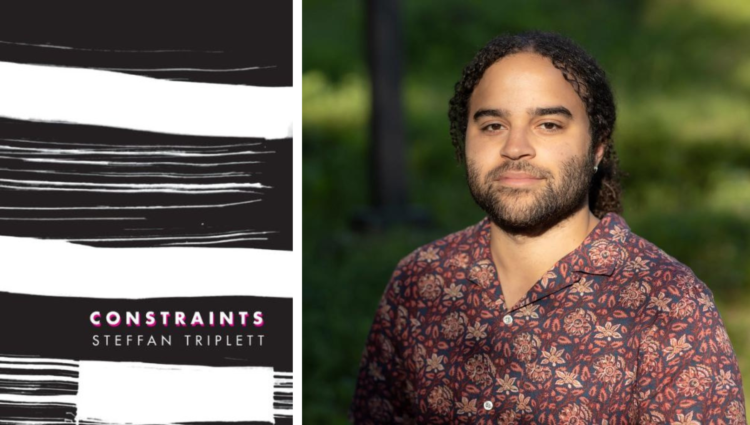

Playing with and reflecting on restriction is the main consideration of Steffan Triplett’s Constraints, published by The Diagram earlier this year in February. In his chapbook of six personal essays, Triplett touches on a range of restrictions related to his sexual identity, politics, and race while also imposing his creative constraints. The pieces are specific to his own experiences of growing up and interrogating what is “normal” in the world. As I read, I found myself remembering similar anxieties of growing up as a gay kid in the ’00s, and the mixture of relief, regret, and shame of being too vulnerable with a friend. Like Triplett, I yearn for a time in my personal and our collective past when joy, happiness, and ease seemed simpler.

Triplett explores the tension between the troubling constraints of his present and his desire for a past that is ostensibly more straightforward. In “Disgregate,” Triplett communicates the desire for a simpler time in which all he wanted was his grandmother’s love and to buy a PlayStation with his spelling bee winnings because “life was as simple as that.” But other essays in the collection demonstrate that even a childhood with simple desires is not without its traumas and fears.

Triplett complicates this idea of memory and nostalgia in “Quest.” This short essay is rife with childhood anxieties related to the authority of religion. He worries that his parents’ visits to a casino will prevent their salvation and prays that a young child he sees in the casino’s jungle gym will be spared from damnation. Even a childhood with a PlayStation is not without worry and anxiety.

The threats of damnation follow him through high school, this time, turning inward. In “On a Bridge,” Triplett recounts the stomach-churning anxieties of a young Christian boy who believes that kissing his friend Marc is a sin that will lead to his eternal damnation. The church in the writer’s hometown looms large while he renders his experience of simultaneous dread and desire visceral by bringing it into the body: “An invisible rope pulled my stomach towards Marc, though I made sure not to stand too close.” We feel their teeth smacking together as they kiss for the first time, and how the narrator’s heartbeat quickens as he checks if their parents might catch him and his friend in an embrace. Here, it is the fear of parental and religious retribution that leads the writer to restrict himself from who he is and what he desires.

Triplett’s adulthood is also hounded with an anxiety that exhausts and a worry that extends beyond himself to marginalized people. In “Bookshelf,” Triplett alludes to the 2016 US election without naming candidates. But readers will know what is meant by “the map has bled enough,” especially as he writes of being a Black gay man and not knowing how to interact as a teacher with a group of white students who might have voted for this unnamed president-elect. Triplett creates unease through carefully rendered anxiety and exhaustion. We leave the essay feeling as the writer did: ready to take off one’s work clothes and find refuge in a bed.

Despite the worries and the exhaustion of being a gay, Black man, the last essay offers a glimpse of the possibilities of respite. “Here,” reads like journal entries of his time in a writer’s residency in a rural setting. Climate anxiety appears as little storm clouds while the narrator grounds himself in close observation of birds, pollen, and cats. Triplett resists the crush of climate change by grounding himself in the present and yearning to be there for the people who have mattered to him the most, even if they have since spun away from his life. Indeed, this is the only essay in which the writer seems to be working to step away from constraints: “Maybe, just maybe, I can shake this all off, then out.”

Triplett succeeds at quiet inspiration in the last essay, rendering the beginning of resisting our traumas by being present in a changing world. Where the other essays pound with anxiety, worry, and a desire for a simpler past, the last essay’s flourishing prose offers a glimpse into the writer’s practice when the constraints are more self than societally imposed. We see what happens when the author removes himself from the eyes of the church, white hegemony, and academic institutions and gets to focus on his art. He writes so much that a spider weaves a web on his arms. He is still enough to notice and write with glowing prose:

Some neighbors brought us vases of flowers from a garden. They’re beautiful, and I imagine a garden with rows and rows of all types of color. Crimson, maroon, a vivid magenta. That there’s such color in natural flora, not just in a flower shop, is shocking to me. Some anthers and pollen fall onto my desk and I’m taken with such color. More gold than the sun can ever be.

Steffan Triplett, “Here”

Triplett ends his collection of mostly anxiety-riddled essays with resolve. Although it is unjust that he must separate himself from society, religion, and politics to find community, solace, and presence, Triplett asks what might be possible if our sole constraints were those of our creation.

The collection inspires me to take a closer look at my worries so that I may accept and work with them rather than against them. How might I take my personal anxieties—fears of nihilism, not finding a partner, having to flee my own country like my ancestors did—and transmute them into urgent material?

In the endnotes, Triplett shares that each piece has a different creative constraint. He does not note what the constraints are. I could see how Triplett, a trained poet, played with formatting, space, and rhythm, and I initially wished for the constraints in each essay to be explicit. I went back through the essays multiple times and could only guess at the creative constraints.

I came away from Constraints with an understanding that there is value in an artist’s puzzling self-imposed restrictions. After all, constraints may be invisible to us, but exist all the same.

Constraints by Steffan Triplett was published by The Diagram in February 2024, and is available wherever books are sold.

Steffan Triplett is a Black nonfiction writer from Joplin, Missouri. He is the author of the forthcoming hybrid memoir Bad Forecast (September 2024, Essay Press) and the essay chapbook Constraints. His essays and cultural criticism have appeared or are forthcoming in Vulture, Longreads, Lit Hub, Alta Journal, and It Came from the Closet: Queer Reflections on Horror. He is the Managing Director of the Center for African American Poetry and Poetics (CAAPP) and a Teaching Assistant Professor at the University of Pittsburgh.

Winson Law (he/him) is an emerging writer of fiction and poetry. He has mentored youth in juvenile detention through the Pongo Project Project and served as a board member for Seattle City of Literature. He resides in the Seattle area and has previously worked in technology, nonprofit, and bakeries. With a degree in geography from Middlebury College and knowledge of multiple languages, he seeks the eccentric and universal in his writing. Reach out via winsonklaw.com