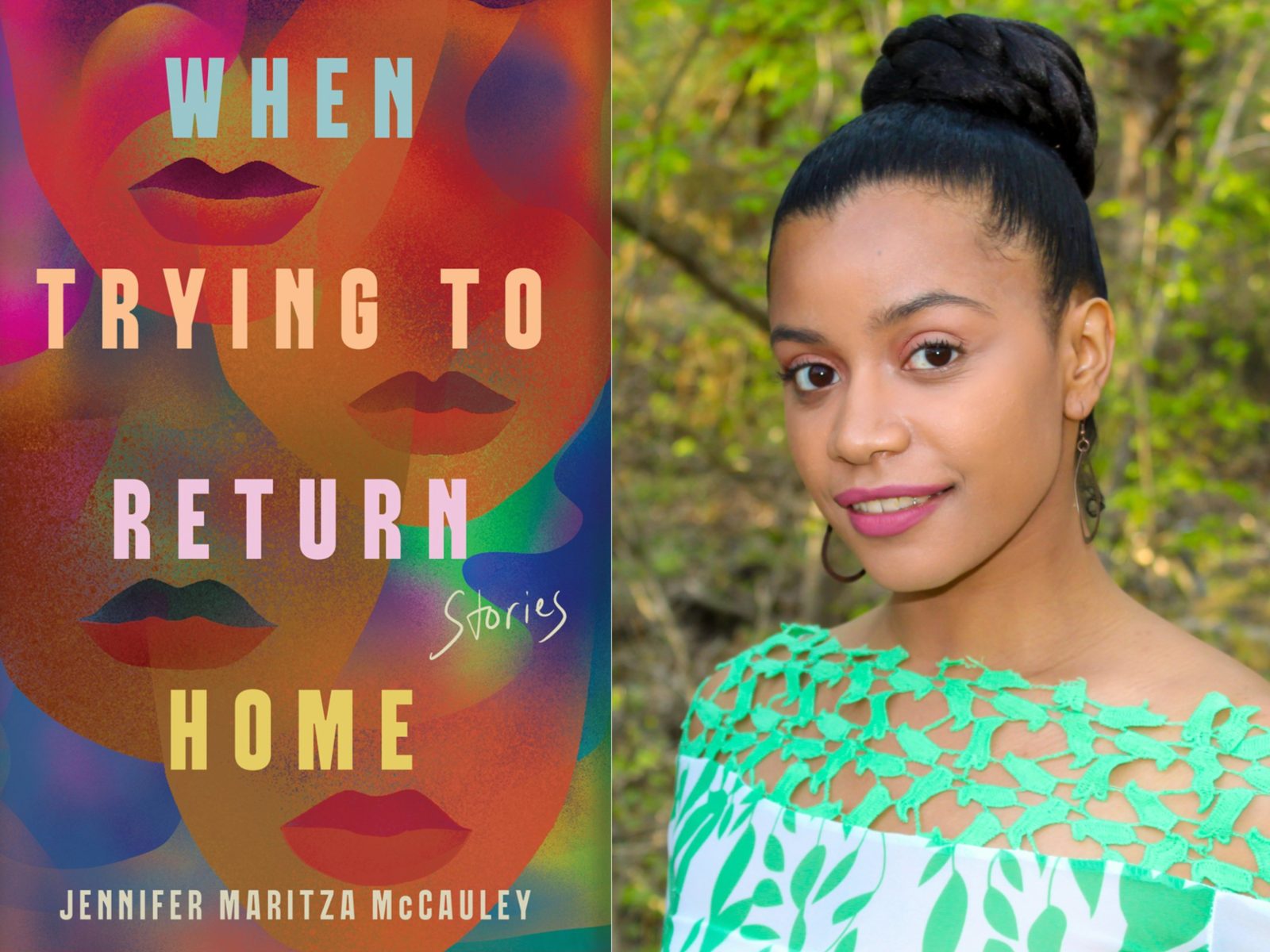

For many of us, home can be a complicated place. It is amorphous and, as a result, oftentimes elusive, a place that can both sustain and harm us. Jennifer Martiza McCauley explores the concept of home in her moving debut short story collection, WHEN TRYING TO RETURN HOME. I recently spoke to the author about the characters that shape her new book and their complex relationship to some of the central themes of her collection. What is home, and what loyalty, if any, do we owe to the people and places that shape us?

Melissa: We see your characters tackle what it means to belong – not just to a physical place, but within the context of their families and their own Black and Latine communities. We perhaps see this most acutely in The Missing One. Brown v. Board of Education recently came down, and in this story, we meet Kal who is struggling to find his place at his recently integrated school. He also discovers that the unhoused man near his bus stop is actually his half-sibling. Everyone in the family and his community seems deeply invested in Kal and his success, but they completely shun his half-sibling, Bags. Why was it important for you to show this contrast and why specifically in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education?

Jennifer: I wanted to have two different trajectories for both of these brothers. Kal is the son who is embraced by the community. His proximity to a white school underscores their support of him, even though Kal is struggling at that school. Then you have Bags who is the complete opposite. I wanted to show this juxtaposition: how we treat unhoused people and those who do not follow a traditional path versus someone like Kal who is doing what the community and society expects him to do. And showing this immediately after Brown v. Board of Ed was particularly important to me. My father was actually one of the first Black children to attend an integrated school in St. Louis. I always had a story arc in my mind about a Black boy trying to navigate an integrated school and community.

Melissa: An adult Kal makes an appearance in Fevers, and we also see his other brother, Abbot. We get the sense that Kal has moved on from his youth and hometown, but comes home when he’s ill. There’s resentment on Abbot’s part, which is understandable on some level. Yet, going home is something we tend to do when we need healing, even if those places have harmed us and even when we’re unaware of the people we’ve hurt there too.

Jennifer: Kal is the shining, golden child of the community and his family. Abbot recognizes that Kal was able to achieve what he achieved because he had people like Abbot helping him through that process. The whole family supported Kal. Abbot was always looking out for him. He made sure he was beating up the guys that were harming his little brother. He understands the result of all that support, which is that Kal goes off to have this career in Boston. But Kal is not okay – that career is killing him. All Abbot sees, though, is Kal going out and doing great things. There’s going to be some resentment there even though success is not all that it appears to be.

Melissa: We see another set of siblings in Estelle and Mavis. The pair search for home, in their own way, in I Don’t Know Where I’m Bound and Liberation Day. The sisters are bound to each other, but no specific place. They’ve lived in Nashville and Miami and New Orleans. They’re each looking for a place, for someone, to belong to or belong to them.

Jennifer: Estelle and Mavis have a special bond. Their relationship goes beyond the other people they’re around and the places they’ve lived. It exists outside of their love interests. They are a love story in and of themselves. They are siblings – that is the bond. If they weren’t sisters, they might actually be turned off by each other. But I can see them having a relationship nonetheless because they complement each other so well. I wanted to show that sisterhood bond. They don’t need to have a home because they end up finding it in each other.

Melissa: We have a more complicated bond in Torsion. Claudia is very much torn between following her own moral compass and her loyalty to her mother as they attempt to bring home her disabled brother. We see Claudia’s devotion to her mother almost propelled by her mother’s devotion to her other child. What did you want to explore there?

Jennifer: I wanted to explore how mother-daughter relationships and familial bonds can be so overwhelming that we can be blinded by our devotion to those who raised us. Claudia is self-aware; she knows her love for her mother and fidelity to her is going to destroy her, but she acquiesces. That’s the strongest love she knows. I do think Mama genuinely loves her daughter and son. It’s just an oppressive kind of love.

Melissa: We also see Estelle in Good Guys, where we meet Alejandro. He believes that he and a few friends are the “good guys” because they want to protect Estelle, who’s chosen to become a nun, from the advances of another classmate. But is Alejandro actually a “good guy” or is he simply trying to find a way to get into Estelle’s good graces?

Jennifer: Alejandro is trying to be a good person, but he thinks there’s a checklist of what a good person is. He’s not a bad guy. He’s just trying to be the sort of person who will make his parents proud. But he is a young man and he has this Catholic guilt that he wrestles with. There’s a conflict between what comes out of his mouth versus what’s in his head, and he has this conflict throughout the story. He’s someone who is searching to belong through another person because he doesn’t have that stability at home.

Melissa: We do see someone who might arguably be considered a “bad guy” in La Espera.

Jennifer: Yes, Carlos, and he is complex. In that story, I wanted to show the ramifications of frustrated love. Carlos is so caught up in his relationships with two sisters that he doesn’t have the agency to take charge. It overwhelms him, and he lets it drag. I wanted to show sisters who come back together at the end despite the complexities of what they went through. I wanted to get everyone’s point of view in fragments and write a frustrated love story from multiple perspectives. Colorism comes into play as well.

Melissa: We keep searching for the familiar – that sense of belonging – even when what felt like belonging is gone. There’s a desire to “go home” in both Last Saints and When Trying to Return Home, but in two very different ways. The physical home in Last Saints doesn’t exist anymore. The town of Emmaus is gone, but the memory and the essence of the place still reside inside Potato and Sugar Red. And in When Trying to Return Home, we see this longing for a loved one. “Home” is, in some ways, rooted in that loss.

Jennifer: I wanted to explore how home can be a person and encapsulate many kinds of homes. In When Trying to Return Home, the mom is the narrator’s home. Culture is represented in her mother as well. When she loses her, and goes back to South Florida, she looks for that feeling of home in other people. Similarly, in Last Saints, we lose both the people that represented home and the actual town. What we do, as humans, is look for home in people as much as we do in places.

Melissa Rivero is the author of The Affairs of the Falcóns and the forthcoming Flores and Miss Paula (Ecco/HarperCollins). She won the 2019 New American Voices Award, a 2020 International Latino Book Award, and was longlisted for the PEN/Hemingway Award for Debut Novel, the Center for Fiction’s First Novel Prize, and the Aspen Words Literary Prize. Born in Lima, Peru and raised in Brooklyn, she is a graduate of NYU and Brooklyn Law School, where she was an editor of the Brooklyn Law Review. Melissa still lives in Brooklyn with her family.