I

After a lifetime of smoking Virginia Slims, my grandmother was dying of lung cancer in the oncology ward of Milwaukee’s Aurora Sinai. It was the Fourth of July. My Aunt Patty and I were sitting in the hospital cafeteria sharing a lukewarm plate of Salisbury steak and waxed green beans. We were supposed to contact the priest to deliver last rites as soon as we finished eating dinner. I can’t say I loved Grammy Livy, but I can say I felt sad. I drank a little carton of milk as if I were in elementary school, and my aunt drank a little airline bottle of Maker’s Mark whiskey as if it were normal.

“Don’t tell your mother,” Aunt Patty winked, blotting her lipstick with a paper napkin. I noticed that her hands were trembling. Of the two of them, my mother was the more accomplished at handling death, having already buried my older brother. And as everyone knows, losing a parent is a piece of cake compared to losing a child. Right then, my mother was upstairs on the fourth floor, attending my grandmother. That’s just who my mother was—a caretaker.

Aunt Patty inspected my face. “You know, you look a lot like her.”

“Like who?”

“Your mother.”

“No I don’t,” I said. “You do.” Aunt Patty had a wider jaw, though, was bigger boned, half a foot taller, and wore so much makeup you could hardly tell she was my mother’s sister. After the face-lift Patty got in the mideighties, my brother, Bernie, described her look as “a transvestite channeling Lucille Ball.” But that was harsh. It would be more accurate to say Patty looked like an anchorwoman.

She enjoyed a successful career as a self-made motivational speaker. Underneath her alterations, she had my mother’s pretty face. Or a face that used to be pretty.

To end the conversation about genes, I sang along with James Cagney, who was strutting on the flickering black-and-white TV bolted to the wall behind Aunt Patty. I am a Yankee Doodle Dandy!

But Aunt Patty wasn’t to be deterred. “You didn’t know your mom when she was your age. You look just like her in the eyes and around the mouth. Plus, she always held her head in her hand with her fingers spread over her face just like you’re doing right now. I’m telling you—it’s uncanny.”

I moved my hand and sat on it. I preferred to think I took after my father. “Mom has blue eyes. Mine are brown.”

“Do you realize you’re behaving like a twelve-year-old?”

“I am not!”

I was twenty. It was 1998.

“It doesn’t matter what color your eyes are. They’re exactly like hers.”

“Our hair is different. See?” I undid my ponytail and shook out my hair. “Wavy. Black.”

My mother’s hair turned white after my brother’s accident. Before that it was the color of a field mouse. The transformation happened almost overnight. It’s funny how time works. She hovered over Bernie’s broken body, praying to her God and all her saints that her son would wake up, while I went through our family albums reordering the sequence of photographs. In my memory those long weeks spread out like an ocean. Or maybe not ocean. Maybe more like a lake of time—a great lapping one, like Lake Michigan, where my mom and Aunt Patty built sandcastles as girls.

My point is that during this same interminable period of despair, my mother’s hair seemed to turn white in an instant. In the time it takes for a drop of water to drip from a leaky faucet—plop!—my brother was dead, my mother old. This is proof that time isn’t linear. It can be both fast and slow at the same time.

“Do you know what I’m going to do?” Aunt Patty asked.

“You’re going to call Father O’Connell,” I guessed.

“Nice try but no cigar,” she said. “I’m going to tell you the story of how your parents met.”

My parents had always been evasive about this. I had a bad feeling about what Aunt Patty was going to say, but I put down my plastic fork anyway to demonstrate I was ready to listen.

“It was 1968,” she began. “They were both students at Marquette University. Your father had a full scholarship because they were desperate for smart Negroes, and your mother—”

“Nobody says ‘Negroes’ anymore, Aunt Patty,” I interrupted.

“I’m not talking about now. I’m talking about 1968.”

“I’m not so sure we were called Negroes in 1968 either.”

I spoke collectively because it made me feel better. There had been no we for me since my brother’s death. I didn’t belong to either of my parents, and nobody who looked at my face would ever think to describe me as a Negro.

“Alright, Miss Persnickety, do you want to hear the story or don’t you?”

I did and I didn’t. The bad feeling sat in my stomach like one of those toys in a capsule Bernie and I used to get out of the gumball machine at ShopRite while our mother sorted through coupons for Palmolive and raisin bran. Back home, we’d drop the plastic pill in a glass of water, and a sponge in the shape of a dinosaur would magically unfurl before our eyes. But I couldn’t tell my aunt that on account of whatever she might reveal, I was pregnant with dinosaur dread.

“Your mother worked two jobs to pay for her tuition,” Aunt Patty continued. “She was a salesgirl in the shoe department at Gimbel’s, and she also worked on the assembly line at the meat-rendering plant down under the Sixteenth Street viaduct. Both those places are long gone. Times have changed. If you had an interest in going to sightsee the place where your mother used to process cow carcasses from the slaughterhouse, do you know what you’d find today?”

“Obviously not.”

“Cut the sarcasm. It isn’t becoming.”

“Sorry. Go on.”

“Well, I’m not so sure you’re mature enough. ‘What does your Aunt Patty know anyway? She never even went to college.’ That’s what you’re thinking, right? ‘What does your old Aunt Patty know about anything?’”

She was so good with the guilt. I didn’t even have to fake being contrite. “Please tell me,” I said. “What would I find today?”

“The Potawatomi Bingo Casino.”

The Maker’s Mark was veering her offtrack. “Okay,” I said, “but how did my parents meet?”

“You need to understand the landscape of the times that brought them together. Milwaukee was one of the most segregated cities in the country, and it still is. The Menomonee River valley divided the city in half like the Mason-Dixon Line. Give me that. I’ll show you.”

“This?” I looked down at the paper from my drinking straw, which I’d been wrapping around my index finger like a bandage. “Why?”

“Just do as you’re told.”

I gave my aunt the wrapper.

She unrolled it and laid it across the middle of the plate between us, dissecting it in half. “Whites on the south side,” she pointed at the green beans, “blacks on the north in the inner core,” she pointed at the meat. “When your mother wasn’t on her knees measuring people’s feet for dress shoes at Gimbel’s, she was handling raw beef on the floor of this valley,” she pointed at the straw wrapper. “Have you ever smelled a meat-rendering plant?”

“No,” I said. Places like that didn’t exist where I grew up.

“Well, you better hope you never do because they stink to high heaven. You had to be strong to work in a place like that. Most folks couldn’t go near it without gagging on the stench, let alone set foot inside. Most folks would lose their lunch if they did. Your mother had to rinse her hair with rubbing alcohol to get out the stink.”

“If that little child in 503B don’t get a new heart by Tuesday, he gon’ die,” I heard someone say. It was a nurse sitting at the table next to us, talking to another nurse. Cartoon cats in red sneakers slinked across the V-necked shirt of her uniform. With great patience, she dunked a tea bag into a steaming Styrofoam cup over and over and over again.

“Who says?” asked the second nurse. She wore hair extensions, a crucifix, and two-inch acrylic nails painted red, white, and blue in honor, I assumed, of the holiday.

“Doc Arapurakal,” said the first nurse.

“Oh, I’m sorry,” said Aunt Patty. “Did one of those black mammies over there give birth to you?”

“What?”

“Pay attention. Show a little respect. Did you even know your mother worked her way through college?”

“No,” I answered.

Aunt Patty snorted. “Of course not. Did you know she majored in physics and wrote a very important paper about bubbles that was published in a very important scientific journal when she was just your age?”

I shook my head. All of this was news to me. My mother was a housewife when Bernie and I were growing up and an assistant librarian after my father divorced her for one of his graduate students. Not that grief is a contest, but I don’t know whose heart he broke hardest when he pulled that stunt—Bernie’s, mine, or our mother’s.

“Let’s pray on it,” said the second nurse, taking the first nurse’s hands. “Doc Arapurakal don’t know what Jesus has in store.” They closed their eyes. I would have liked to hold hands with them. I would have liked to crack open my rib cage, tear out my heart by the roots, and deliver it to them. “Here,” I would say, “take mine.”

Instead, I asked Aunt Patty if I’d heard her correctly. “Did you say ‘bubbles’?”

“That’s right, kiddo. Your mother studied the surface tension in the walls of bubbles. But you wouldn’t know a thing about it because her thesis adviser published that paper under his name, and she was too humble to make a fuss.”

“What was the name of the journal?”

“That’s not the point, Emma. I’m trying to tell you, there are things about your mother you don’t know.”

This directly challenged a long-standing notion that my father was the more mysterious parent. Bernie and I used to sneak into the drawer on the top right-hand side of the dresser our parents shared. Dad’s drawer contained a loose disarray of tie clips, cuff links, monogrammed handkerchiefs folded in thirds, ticket stubs, buttons, a gold pocket watch with a cracked face, a lint brush, matchbooks, packets of pipe tobacco, pipe cleaners, pipes, a little delft dish full of foreign change, and a tattered black feather, which I believed for years he’d found on the ground and was saving to give me when I did something very, very good.

As for our father’s collection of pipes, my brother and I pretended to smoke them. We sucked on their mouthpieces in order to inhale the sweet taste of tobacco resin, making little kissing noises where his lips had been, where his molars had left chew marks like the ones we made on our number two pencils. “Elementary, my dear Watson,” Bernie would say, holding a pipe in profile like Sherlock Holmes, and we would continue digging through those man-things as if they were invaluable clues. Our mother’s drawer, on the top left-hand side, full of polyester half-slips and panty-hose, did not interest us at all.

After our father left us, she stored a journal of “things to be grateful for” in that drawer. According to Aunt Patty, recording her gratitude would restore our mother’s joy.

Bernie was at the top of the list. I came in second.

We knew next to nothing about our father’s past, whereas we’d been dragged to Milwaukee at fairly regular intervals throughout childhood to visit our mother’s family for baptisms, weddings, and funerals. We always went without our father, who was not welcome in Grammy Livy’s house. This was because our Pops, a vitriolic drunken Irishman, was a lifelong racist, and it was also because our father preferred to stay at home in Princeton with his head in a book.

“Obviously, you know what your father majored in,” Aunt Patty said.

My father was a renowned historian.

Aunt Patty pointed toward an instructional poster of the Heimlich maneuver coming unstuck from the cafeteria wall. “He lived just two blocks that way in a brick building on the corner of Fourteenth and Kilbourn. He liked to sit out on his balcony in a gray fedora hat with a little red feather in the band, watching the sun go down. The girls were crazy about him, even with his clubfoot, because he was taboo. Have you seen pictures of your dad from that time?”

I had.

“Then you know he was a real looker. Needless to say, he was a political activist. Everybody was, back then, because we cared. Not like your generation.”

I opened my mouth to protest but shut it. There was nothing I could say in defense of my generation. Plus, as I said, I didn’t have a we. My family was fractured. I didn’t belong to a race. I didn’t feel connected to anything circumscribed, and certainly nothing as categorical as a generation.

“Don’t think I’m saying our counterculture made us better than you,” Aunt Patty clarified. “I’m not. There was a draft. Sure, we acted because we were disappointed by our parents, but mainly we acted because we were afraid for ourselves. It wasn’t that we were good. It was that we were afraid. A lot of boys were only in college because it meant they didn’t have to go get their ding-a-lings blown off in Da Nang.”

“Not my dad. He couldn’t go because of his foot,” I reminded her. I didn’t like the implication that he was a coward coming from the mouth of a white lady, even if she did happen to be my aunt.

Aunt Patty withdrew a tiny bottle of Bacardi rum from her purse, uncapped it, and downed it in one swig. “You, my dear, have daddy issues,” she burped.

“Where did you get those?” I asked, referring to the little liquor bottles. She sett hem next to each other on the table resolutely, like salt and pepper shakers, like husband and wife.

“Don’t change the subject, Emma. I’m telling a story. Where was I?”

“My dad was a political activist. . . .”

“And there was a credibility about him because of his color that made the other students want to follow him. There’s a ten-cent word for that quality . . .” prompted Aunt Patty.

“Gravitas?”

“That’s it.”

I was full of ten-cent words because Grammy Livy mailed me her Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary when I was confirmed in the Catholic faith. It had been awarded to her in 1938 when she graduated from Notre Dame High School for Girls, and it was the only gift she ever gave me. Written on the frontispiece in carefulc alligraphy were the words: To Olivia Lenore O’Faolain, for Excellent Deportment. The sound of her name was delicious to me at thirteen. I spoke it in the privacy of my room over and over again, tasting the Ls: Olivia Lenore! Oh, Olivia Lenore! In between partipris and passion I found a purple flower pressed as thin as tissue paper. I assumed it was a pasqueflower, which was defined on that page, but it crumbled into dust at the touch, so I couldn’t be sure.

“Gra-vi-tas,” my Aunt Patty repeated, drawing out the syllables as she dabbed at a spot of gravy on her rayon blouse. “Your dad was the local Martin Luther King. He helped organize the takeover of O’Hara Hall and the equal housing marches from the north side over the Sixteenth Street viaduct into Polishtown.” Aunt Patty picked up a green bean and laid it perpendicularly over my straw wrapper.

“What’s that supposed to be?” I asked.

“That’s the viaduct, smart aleck. They named this bridge after the priest who led the march, but they could just as easily have named it after your dad. You have no idea how hostile it was then. My God, the kind of hatred white people were spitting when the Negroes started demanding their rights—‘They’ll be raping us!’ ‘Wewant slaves!’—that kind of thing. They were in a total state of panic. When your dad crossed over that bridge to protest, those folks were burning effigies, throwing chunks of concrete, rioting. You’re not eating. Have some more steak.”

I looked down at the plate of meat and gravy. Then I looked at the two nurses, who were still praying for the boy with the hole in his heart. I couldn’t stand hospitals. “I’m not really hungry.”

“Me neither.” My aunt looked at her empty little bottles with sadness.

“Were you politically active?”

“Me? No. Not really. I got knocked up with your cousin, Crystal, when I was eighteen, so . . .” she drifted.

I envisioned my mother in a hairnet and some sort of blood-spattered butcher’s apron at the door of the factory on the polluted riverbank, gazing up from the valley floor at the bridge my aunt described, and my father marching over it like Moses leading the Israelites behind him. I imagined the rocks and insults whizzing about his head as he pushed forward to the south side into the mob that reviled him. It was easy for me to see why my mother fell in love with him. He was righteous. But I could not understand what he saw when he looked down at her from those dizzying heights.

Aunt Patty sighed like a deflating balloon. “He hosted these parties that would go all night. They were very intellectual. Everyone talked about Vietnam and civil rights. Your dad would play Dylan and jazz. Lynn went to one of those parties with her roommate. I can’t remember her name . . . Roxanne? Roberta? She was the Waukesha County beauty queen, not the sharpest knife in the drawer, but your father was screwing her at the time—and that’s where your parents met.”

Aunt Patty removed her paper napkin from her lap and draped it on top of the plate of untouched food as if she were laying a sheet over a corpse.

I considered what I’d just been told. “That’s the story?” I asked. “I don’t get it.”

“What’s not to get?”

The setting was wrong. I would have preferred they fall in love during a march like the one in Aunt Patty’s story. I wanted to witness a flying brick strike the side of my father’s head; for him to be knocked unconscious by the blind cruelty of the world; for my mother to ascend, take his head in her lap like Florence Nightingale, and bravely minister to his wound right there on the bridge. I wanted to hear the mob call her “nigger-lover.” I wanted to see her face coming into focus through his eyes when he came to, and for him to know with certitude that she was the only woman for him. I wanted a theme song. My parents deserved a theme song because they were a metaphor for America’s most optimistic moment. And because my brother and I were the product of that optimism, I wanted Bernie and me to be there like a taste in their mouths when they leaned into each other and kissed.

“Where’s the magic moment?” I asked.

“Magic, shmagic,” scoffed my aunt. “You’re just a kid. What do you know about love? Cinderella and pumpkins. That’s not how it works, princess.”

“Maybe not. But if my dad was going out with my mom’s roommate, why did he dump her for my mom?”

“I never said he was dating the roommate. I said he was screwing her.”

“Fine,” I blushed. “But if he could have any girl he wanted, like you said, how come he picked my mom? Why’d he ask her to marry him? How’d he propose? Why’d she say yes when Grammy and Pops hated him so much for being black?”

Why on earth did my father love my mother? Without realizing it, I had shredded my napkin into an untidy pile of paper bits.

“Boy, do you ask the wrong questions,” said Aunt Patty.

We stared at each other in mutual exasperation.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“You missed the whole point.”

“What was the point, then?”

“The point is that you look exactly like your mother.”

I sighed and put my head in my hand.

My aunt tapped her front teeth with her fingernails, which were bitten nearly to the quick. That wasn’t like her. Neither was the quarter-inch of gray root showing in the part of her dyed red hair. Under the fluorescent cafeteria lights her concealer was an odd shade of orange, not quite thick enough to hide the flush of booze in her face. I’d never seen her so unkempt.

Joan Leslie was singing on the TV screen behind her: “My mother’s name was Mary. She was so good and true. Because her name was Mary, she called me Mary too!”

“Wait a minute,” said my aunt. Her eyes were out of focus. “Wait a minute, that wasn’t it. I told the wrong story.”

“What?”

“Gee, you never cared much for my name before. It was kinda common,” Joan Leslie demurred to James Cagney. “Gee, there’s millions of Marys around.”

“I got it wrong,” Aunt Patty said.

“I didn’t write it for the millions of Marys. I wrote it for one particular, very special Mary,” James Cagney said.

“That’s not how they met?” I asked.

“It’s a wonderful feeling having your name written in music,” trilled Joan Leslie.

Bernie hated this movie. He preferred Cagney as a gangster.

“Nope,” said Aunt Patty.

“Jesus Christ.”

“Hold your horses. I have it now. I remember.”

“Well?”

“They met at Real Chili’s. Over on Wells. You could get a sixty-five-cent bowl of chili on credit there from a middle-aged waitress named Blondie. Blondie had a notorious early life. I believe your father was screwing her too.”

How come I was depending on a recovering alcoholic, tipsy on two prohibited jiggers of liquor, to reveal that precious thing all girls are supposed to know—the original story of their parents’ love? I wanted to hold that story in my hand and feel its golden weight.

I could have continued enumerating the missing elements of the story, but my aunt, who was a mercurial woman, cut me off at the pass. “Seven forty-five,” she said, shifting us back to the present. “It’s time to call the priest! Mother will be dying soon.” She got up from the table and smoothed her skirt. “I think she’ll be relieved not to have to wake up every day and put on pantyhose, don’t you?”

II

I had two choices. The first was to resign myself to Patty’s pragmatic version of events, and that choice depressed the hell out of me. It meant taking the elevator to the fourth floor to watch my grandmother die. The second choice was to go hunting for magic. That meant walking to the Potawatomi Casino and pouring every cent of the little money I had into the slot machines.

I had ten dollars and change burning a hole in my pocket. Yet for all my brattiness, I was a good daughter. I was not a good daughter because I was a good person. I was a good daughter because I was the only child left.

In the elevator ride to the fourth floor where my grandmother lay dying, I thought about the sad fact that most people don’t get to enjoy fame or notoriety in their lifetimes. My father was an exception to this awful rule, and so was my aunt, to some extent. They were both prominent in their circles. They went to conferences. They were paid handsomely to speak before captive audiences. But it seemed to me that the closest most people came to gaining that level of attention was the chapter of their youth when they fell in love and were feverishly, if briefly, adored.

My cousin, Crystal, for example, who worked as an administrative assistant at a pharmaceutical company and was the sort of pear-shaped woman nobody would think to look at twice, spent forty grand on her wedding because it was probably going to be her only moment in the spotlight. The wedding took place in a hotel ballroom outfitted with ice swans and a grand staircase that lit up step by step like a rainbow when the newlyweds descended hand in hand. My cousin is divorced now. I get that her wedding was a paragon of tackiness and a reprehensible waste of money. But on that particular day, Crystal shone like the sun under the tiara pinned in her big frosted hair. The problem with Aunt Patty’s story about my parents was that it hadn’t allowed me to see my mother, who would never be famous, crowned by love.

I hovered in the doorway of 423D and observed her. A plump middle-aged woman in a baggy denim dress with her white hair fastened in a plastic clip. She was trying to make my grandmother take a sip of water.

“You’re doing it all wrong,” rasped Grammy Livy, slapping at my mother’s hands. Her words came out slurred because the right half of her mouth was drooping along with that whole side of her face. “Now look what you did,” she snapped when the cup slipped from my mother’s grasp and spilled on the bed. “Clumsy.”

There were a few reasons why I didn’t love Grammy Livy. One of them was that I didn’t like the way she spoke to my mother. Another had to do with that dictionary. Two years after Grammy Livy mailed it to me, she explained “with deep regret” that she’d made a mistake. She was on a new medication when she sent it and not in her right mind. She wanted me to return it. Before doing so, I looked up the word regret to better understand her, and my mom invited Bernie to spit inside its pages. He was so talented at hocking phlegm! Our mom thought I would enjoy that, and as a matter of fact, I did.

My grandmother fell backward in a coughing fit, clutching one bony hand to her shrunken chest, the phlegm rattling in the drum of her throat. Her eyelids were bluish, and the slack side of her face was purple from where it had struck her kitchen floor. “Don’t enter any beauty contests this week, Grammy,” I’d said earlier. It was meant to be a joke, something to lighten the mood, the sort of joke Bernie would’ve had everybody in stitches over, but nobody laughed when I said it. She had an oxygen tube in her nose and was hooked by her limp right arm to an IV. She wore a thin cotton gown, the same exact kind they put Bernie in on the night of his accident.

“Is she okay?” I asked to announce myself, though I knew she wasn’t. The cancer had started in my grandmother’s lungs and metastasized to her liver and to her brain, where two tumors festered, big as prunes. All this malignancy went undetected for years until one of the tumors gave her the stroke that landed her in Aurora Sinai. They’d done a couple rounds of radiation on her, but there was no point in chemotherapy. According to the doctors, Grammy Livy was likely to die any minute. It was a miracle she was still alive and able to talk. There wouldn’t even be time to segue into hospice care.

“Hi, bug,” said my mother. “Did you call the priest?”

“Patty’s doing it,” I answered. I was afraid to step into the room. It smelled like urine and my grandmother’s Jean Naté powder. “Can I do anything to help?” I asked lamely.

“For the love of God, tell her to get me a cigarette,” Grammy Livy wheezed.

“You know you can’t smoke in here, Mom,” my mother said, stroking Grammy Livy’s limp hand and swiping at the wet spot with a towel.

“I’m dying,” Grammy Livy declared.

“There, there,” said my mom.

“What kind of dress is that to wear to your mother’s deathbed?” Grammy Livy coughed. “It isn’t flattering.”

I hated her. I hated her so much in that moment. Not my grandmother, who had always known precisely what to say to cut a person down and who was dying, after all, but my mother, for putting up with it. Why didn’t she ever stand up for herself? Why did she have to be a martyr?

“Don’t talk to her like that,” I warned my grandmother.

She looked startled to hear me speak. “What did you say?” she wheezed.

“I’d appreciate it if you didn’t talk to my mom like that.”

“Emma!” my mother cried, as if I’d been the one to say something rude.

“What?” I seethed. “She should be grateful. You’re helping her. Even if you were dressed in a potato sack she should be grateful!”

“Stop it,” my mother said, giving me the pointed look she used to give me when I couldn’t stop squirming in my itchy wool tights during mass at St. Paul’s church. Then she turned away from me. “Let’s try drinking a little more water,” she encouraged, as if Grammy Livy hadn’t just insulted her. As if I hadn’t just defended her. Slowly, selflessly, she refilled the cup with the sweating plastic pitcher on the bedside table and, with a tenderness that pained me, brought it to my grandmother’s lips.

I spun on my heel and left. No wonder my father left her, I thought. She was a pushover. The last thing in the world I wanted was to be like my mother. I thought I would suffocate in the elevator on the way back downstairs, and I was bristling with resentment when I stepped out of the air-conditioned hospital into the humid, fading day. The electric doors sucked closed behind me.

Suddenly everything was different. Anything was possible. I felt like running, soI did. The casino wasn’t far off, according to Patty’s impromptu map on our dinner plate. I could find it. There was a slender possibility I could get rich and run away to begin a brand-new life in which I wasn’t the sister of a dead boy and the daughter of a man who couldn’t see me. My skin was indiscriminate enough. I could be Egyptian. I could be Puerto Rican. I could be from Cape Verde. I could be anyone. All I had to do was go find that unity bridge and wander beneath it.

I turned south on Twelfth Street, ran down to the campus my parents had attended, and found myself smack-dab in the middle of a parade. Hundreds of people were strolling east to the lakefront to watch the fireworks. They rolled along Wisconsin Avenue with easy Midwestern strides—overweight, pleasant, smiling. They carried picnic baskets, blankets, and coolers. They pushed their children in strollers or led them by the hand. The children waved little postcard-sized American flags on skewers and wore plastic glow-in-the-dark necklaces. They all looked so happy.

As for Marquette’s campus, it was urban and gritty compared to Princeton’s, where I grew up. On either side of Wisconsin Avenue were Marquette’s classroom buildings, the St. Joan of Arc Chapel, the Gesu Church with its rosetta window, the library where my parents studied when they were my age—maybe sharing a carrel, maybe going to third base in the stacks, who knows?

There I stood on the grassy median in the middle of the road. The sun was dropping behind the people like a blood orange, blazingly gorgeous on account of the pollution spewing from the brewery smokestacks. Snatches of conversation hung in the air around me:

The secret is mayonnaise.

. . . and that’s when my breasts stopped leaking.

It’s your fault if we get a bad spot this year. I was ready to leave two hours ago.

Did you pack his inhaler, Johanna, or are you a moron?

Fifteen years before this, on the Fourth of July, I was five. Bernie was six, sitting cross-legged on the soccer field amid the fireflies, sucking on a rocket pop. My mother took a picture of him beaming into the flash, with the blue popsicle juice running down his chin.

I ride on my father’s shoulders, with my hands in the wool of his hair, to be closer to the fireworks. My mouth hangs open as I gaze at the sky. I have a pronounced overbite from too much thumb sucking. My father has seen this show staged dozens of times before. It bores him. He holds loosely on to one of my ankles, distracted by something outside the frame. Bernie and I are too young to remember the previous year’s fireworks. We watch them, he and I—the distant phosphorescent sizzle of fireworks falling upward like stars trying to get back home, sea anemones blooming outward on the ocean floor, the shrapnel of exploding grenades.

To get to the casino I had to go west, which meant navigating against the current of people. I felt strange doing that. Wayward. I was moving against the natural order of things, the hand of a clock going the wrong direction. I walked along the median so nobody would brush against me. Like a school of fish, they parted.

I could have been anyone. I was invisible. I wasn’t even there.

At Sixteenth Street I turned left and continued south over the cross-pit of a monstrous expressway buzzing with traffic. Soon the valley opened up beneath me. I continued along the bridge spanning it, assuming that this was the viaduct, though the bridge was much longer than I’d imagined—a mile long or longer, I don’t know. It was endless.

Four stories below were a boarded-up cooperage, a truck yard full of banged-up cargo bays, and a smattering of sooty warehouses with shattered windows. The bridge passed above a field of crushed auto grilles and hoods, aluminum scrap, hub-caps, and great wooden spools of wire and chain—the carcasses of industry. I passed over a railroad yard that reminded me of Bernie’s train set. The shells of empty boxcars cast long shadows in the dying sun.

City of Beer and Bratwurst! I spat over the edge and watched my saliva fall into the river of my aunt’s story, but there were no casino lights twinkling on its shore. Instead there were granaries, huge mounds of coal, ship-loading equipment, and a crumbling brick factory. The narrow waterway looked more like an industrial sewer than a river, its oily surface all puckered by wind. I stopped in the middle of the bridge, feeling uneasy. Had I gotten the streets mixed up? Milwaukee was full of tributaries and footbridges. Was I on the wrong one?

The four-faced clock tower on the skyline to the east told me it was half past eight but there was nobody around to ask for directions. A barge floated beneath me along that lick of water, sounding its foghorn, slow as a dream.

It was the plaintive sound of the Dinky shuttle train on its nightly journey to and from Princeton Junction—a sad wolf howl that used to pull at the edge of my sleep when I was a girl, warning me of something I couldn’t name until Bernie died, and even then couldn’t speak of. Night was coming. I was lost and alone.

A stench rose from the valley floor. I muted my nose and mouth with my palm to keep from inhaling the putrid odor. Gagging, I turned to retrace my steps, but it was too late. The smell was already inside me.

I wondered if Grammy Livy had given up the ghost. I wasn’t ready to find out. I was still angry. Driven by the smell of rotting flesh, I staggered back up Sixteenth Street, over the railroad tracks, above the interstate, and past the campus.

A half hour earlier the downtown streets had been clogged; now they were deserted. Not even a city bus, not even the caw of a seagull. I was alone with the sound of my breath and my Keds pounding the sidewalk as I ran. I was my own crepuscular shadow. The sky was approaching the color of sharkskin. I stopped when I saw the sign for Kilbourn Avenue. I turned right and walked the next two blocks in a kind of slow anguish. Bernie, Bernie, I was thinking. Who was I without him? I would have sold my soul to bring him back. At the corner of Fourteenth Street I held my breath and dared to look up.

There in the afterdusk, on the third-story balcony of a brick L-shaped building, sat my father in a gray fedora with a little red feather in the band. He had his barefeet propped up on an apple crate and was the same age as me.

My father was backlit by the light in his room, but even in silhouette, I knew it was him. He was reading a book. I stood in the near dark, gazing up at him. Then the streetlights snapped on, and I cleared my throat.

“Hey,” I called. “Bernard!”

He didn’t hear me. Maybe he couldn’t hear me. Maybe I was allowed only to observe the past and not to interact with it.

I fixed my hair.

The soles of my father’s feet were uncalloused, the color of salmon skin. His feet were crossed at the ankle, the bad foot balanced over the good one. His jeans were ripped at the knee. His white undershirt was stained at the armpits. My father yawned, scratched his chest, and then turned a page in his book.

“Bernard Boudreaux!” I called. He looked down at me through his glasses. He was ninety pounds lighter and thirty years younger than the man I knew, and he had my brother’s face.

He reached into his pocket and tossed a set of keys through the black wrought-iron balcony bars. Elated, I watched the perfect arc the keys made in the air. I caught them. I caught them! I felt their golden weight in the palm of my hand.

“You’re late,” he said.

III

Shortly after Grammy Livy died, I went looking for the thesis my mother’s adviser published under his name. It took me a few years, but I found it. Its title is “The Structure of Bubbles.”

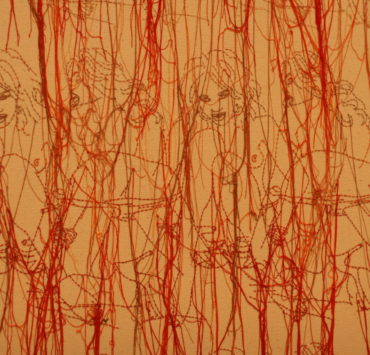

The world-famous mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot once referred to my mother’s thesis as an instrumental document in his discovery of the Mandelbrot set: zn+1 = znÐ + c. For this equation he’s known as “the father of fractal geometry.” Fractals, like the one described by the Mandelbrot set, are shapes that can be subdivided into parts that resemble the whole but never exactly repeat, a property called “self-similarity.” This is the property, and the equation, by which I have partially come to understand what happened in my father’s apartment.

My father must have been listening to the sound of my footsteps in the narrow stairwell because when I reached the third-floor landing, he called, “Come on in, Lynn. The door is open.”

So that was it. He had mistaken me for my mother.

I entered my father’s studio apartment and flipped on the light. He was still out on the balcony. I saw his legs through the open sliding glass door on the far wall. His feet were propped up on the apple crate, and I felt a twinge of disappointment that he hadn’t risen to greet me.

Being in his room was like being in Dad’s drawer on a larger scale. It smelled of smoke, Leavitt & Pierce’s black and gold blend, a smell I still associate with manhood. But it also smelled like a boy’s room, like Bernie, like sweaty socks. I picked one of these up from the floorboards and held it to my nose while watching my father’s legs. The rest of him was obscured by a shabby brown curtain. He wanted me to join him, but what would I say? I tried to remember my US history. Had Martin Luther King been assassinated yet? Was my father living in a hopeful world or a fallen one

His books were displayed on shelves he’d fashioned out of two-by-fours and bricks. There was a beat-up cane chair at a scratched metal desk and, in the center of the room, a makeshift dining table made from a large wooden spool like the ones on the ground of the Menomonee River valley. In a corner on the floor was a mattress with a Mexican blanket and a tangle of sheets. Along the grease-splattered wall to my left was a Pullman kitchen with a sink full of crusty plates. The doorless kitchen cupboards were filled with more books. Aquinas, Hume, Kant. I let my hands skim over as many of their spines as I could. The Souls of Black Folk, Invisible Man, Notes of a Native Son. Mouse droppings sprinkled the kitchen countertop like black sesame seeds. I turned on the faucet, and a rusty gush of water came belching out. I held my hand beneath it to make sure it was real, and it was.

Above the sink a little grimy window overlooked an air shaft. A baby fern in a little clay flowerpot sat on the windowsill. I wondered if it was from my mother. That would be like her, to give him a plant. It was the only nod toward domesticity in his space, aside from the curtain dividing us, and since it was practically dead I watered it in the sink. To the right of the window on the wall above the stovetop hung a strip of lime green flypaper, flecked with the delicate corpses of insects. I touched that too. Even his dead flies enchanted me.

“Lynn?” he called again from the balcony.

“Just a second!” I stalled, overwhelmed.

It was the room of a starving student, but I knew about the lint brush he would pass over the sleeves of his fine suits, the tie clips he would clip onto his silk ties, the cuff links he would pass through the eyeholes of his stiff linen cuffs, and the elegant gold pocket watch (although the watch would be broken by the time Bernie and I fished it from his drawer and secretly fingered its face). I knew about the beautiful Italian suit he would wear to my brother’s funeral. I knew about all that, though none of it had come to pass, and so this room, the antechamber to our life, felt like a stage set. I had an impulse to ransack every prop. I knelt before the miniature refrigerator to the left of the sink and opened it to find a desiccated onion, a bottle of soy sauce, and a box of instant grits. Kneeling there, I opened the soy sauce and took a swig.

“What are you doing?” He was behind me. I flinched, caught in the act of—what exactly?—drinking his soy sauce. In my effort to return it to the fridge as quickly as possible, I spilled some of it on my shirt.

“Lynn?” His voice was terribly near. If I turned around, who would he see? Trembling, I rose, still facing the kitchen wall. As I stood, my eyes met the dripping faucet—plop, plop!—and then my father’s reflection in the little window above the sink; now it was completely dark outside. He was eight, seven, six feet behind me. It was really him. He removed his hat. How much time had sailed by at my grandmother’s deathbed? I didn’t care. My father was limping toward me. I watched his reflection drawing closer. Four feet, three.

“Where have you been?” he asked, not two feet away. His voice was the same, and different. There was something of his native Mississippi in it. Just a trace. It would be gone by the time I knew him. He was close enough that I felt the heat from his body. In a panic, I stepped to the sink, thinking to wash out the stain on my shirt before facing him. And that’s when I saw myself. I caught my own reflection in the little window. There I was, from the collarbone up, and yes, my face was my mother’s.

I was not, in fact, my mother, but we were self-similar. How can I explain this? Imagine a broccoli floret or a frond from a fern like the one on my father’s windowsill—miniature replicas of the whole. Not identical, but similar. These are approximate examples of fractals. They abound in nature. You can find them in mountain ranges, lightning bolts, snowflakes, coastlines, blood vessels, river basins, stock market prices, lungs, galactic clusters, corn-rowed hair, and even certain fireworks displays, like the one that will shortly take place a few blocks away on the shores of Lake Michigan.

In other words, I was my mother’s daughter. The resemblance was undeniable. I had her heavy eyebrows, her dolphin grin, her look of surprise. I closed my eyes, feeling dizzy all of a sudden, and grabbed hold of the counter.

“Are you hungry?” my father asked, laying his hands on my shoulders.

“No,” I lied. I was starving, but what would he have fed me? Grits? I felt the pressure of his palms. He turned me to face him. I was afraid to open my eyes. I was afraid he wouldn’t recognize me, or that he wouldn’t be there at all. So I opened them slowly.

It was really my father, except he didn’t have his beard, and his skin was smoother, and his glasses were different, and he had a hole in his undershirt, and I wasn’t born yet, except here I was. He was smiling, so I smiled back. How well did we know each other?

“Are you okay?” he asked, tucking a piece of my hair behind my ear. Those were really his fingers with the same dark cuticles, except they weren’t as wrinkled at the knuckles and his fingernails weren’t as clean. I wanted to drop to my knees and kiss his deformed foot. I would have done anything to earn his love. “I’m thirsty,” I admitted.

He rinsed out a jelly jar and filled it with tap water. “Here you go.” He smiled. “Thirsty girl.”

I emptied the jar in six gulps and returned it to him, along with his keys. He wiped my mouth with his fingers and drew me to him, nuzzling his face in my neck.

I worried that I stank and, from that worry, laughed.

“Where’ve you been all my life?” he murmured. Had he used the same line on my mother’s roommate?

“I don’t know,” I answered, feeling stupid. It was important that I be smart, that I be smarter and better than my mother so that he wouldn’t leave us.

His hot breath hit the tender space behind my ear. His hands stroked my back up and down with increasing pressure. It felt too good. “Let’s watch the fireworks!” I blurted, pulling away.

My father looked put out. “You’ve got to be kidding me,” he said.

I studied my feet. “I want to watch the fireworks,” I sulked.

“Come here,” he ordered, leading me to the balcony by the hand. He picked up the book he’d been reading from the apple crate where he’d left it and told me to sit down on his stool, which I did. He handed me the book. The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. “There are several speeches in that volume, as you can see,” my father said, pulling a pipe from one pocket and a book of matches from the other.

“Would you hand me my tobacco, please?” My father was clearly annoyed with me. I bent over to pick the packet up from the balcony floor and gave it to him.

“Thank you. Can you guess which one I want you to read?” He sounded like a professor already.

I turned to the table of contents. “‘What the Black Man Wants’?” I asked.

“No,” he sighed.

“‘Fighting Rebels with Only One Hand’?”

“No.” He filled the pipe with tobacco, clenched the stem between his teeth, and lit a match. His face was beardless. He was so young!

“‘The Church and Prejudice’?”

“No, no. Just turn to the page I have marked.”

And that’s when I found it. Holding his place in the book was the black feather.

“Where did you get this?” I asked, holding it up.

“It’s a feather,” my father shrugged.

“Can I have it?” I asked.

He blew out a puff of sweet-smelling smoke and narrowed his eyes. “Why do you want it?”

I twirled it between my finger and thumb. “It’s special to you, isn’t it?”

He looked away from me, down at the street. “You’re being weird,” he said.

“I know. Sorry.”

“I’d like you to read the passage I underlined, Lynn.”

“‘What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?’”

“That’s it. Go on.”

I straightened my posture, which is what my mother does at church right before she recites the Apostles’ Creed, and began: “‘What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us?’”

Here I peeked at my father and found that he was mouthing along with the words. He had memorized them.

“‘I say it with a sad sense of the disparity between us. I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us.’”

“You understand?” my father asked. “This is a sham holiday.”

“Sure,” I said. “I know that.”

“I’m not sure you do,” he scoffed, throwing my mother’s whiteness in my face. It stung. Most people didn’t know I was half black. Only Bernie knew what I was because he was the same thing. I was completely unmoored without him.

“You’re not a slave, though,” I pointed out.

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“You have a full scholarship.”

“I didn’t inherit that privilege, Lynn. I struggled for it.” His voice had a hard edge to it. “You have no idea how I’ve struggled.”

“You’re not the only one,” I snapped. “I work at the meat-rendering plant. Do you even know what that smells like?”

His face closed like a book, and I immediately realized my mistake. It was true I didn’t know anything about his struggles. I wanted to know. “What was it like growing up down South under Jim Crow?” I said softly.

“Hard,” he said. “Real hard.”

I expected him to leave it at that. Not only had I offended him, but I could see how he might consider talking about the hardships of his youth as a kind of whining. He was a man who never suffered whining from his children. When we did so he used to grab us by the shoulders and shake us, harder than he really needed to. I was surprised when he began to speak.

“I was an orphan,” he began.

How could my heart not go out to him then? He was making his eyes more soulful than a hound’s. He was filling his own long silence.

“My father was murdered three months before I was born, and my mother went crazy as a result. They locked her up in an institution. Until I was twelve I lived with my godmother in a shotgun shack. Then I was sent to desegregate a Catholic boarding school because I was smart. My classmates despised me so much I was sure they would kill me. They almost did, but I lived through it. I graduated at the top of my class, and I mean to do the same at Marquette,” he finished.

“You will,” I said. I didn’t doubt anything in my father’s narrative. But compared to my aunt’s, it was so canned and lacking in detail that I couldn’t help feeling disappointed. “Is that the whole story?”

“More or less.” He stepped toward me and placed his hand firmly at the back of my head, which was at the level of his crotch. “Believe me. It was hard.” I had nowhere to look but at the bulge in my father’s pants.

He was trying to seduce me with his history, which was my history as well. To keep from getting confused, I changed the subject. “Do you know what I’m going to do?”

“You’re going to take off your shirt and let me touch your breasts.”

“No, I’m not.” I giggled out of nervousness.

“Yes, you are. This shirt is dirty. See?” He traced the soy sauce stain.

“Never mind that. I’m going to tell you a story.”

My father scratched his scalp. “Is this story going to take long?”

“No,” I promised, “but you may as well take a seat.”

With great reluctance, my father sat down on the apple crate. He squinted at me through his glasses and continued to smoke his pipe.

“You’re going to have two children. A boy, whom you will name after yourself, and a girl, who will look like me.”

“Beautiful, you mean,” he said, reaching for my thigh. I let his hand stay there.

“She’s your daughter,” I reminded him, crossing my arms over my chest. “The boy will be special.”

“What do you mean, ‘special’?”

This was my mother’s term. Bernie was riddled with strange and unclassifiable learning disorders.

“I mean different. Different from other people in ways that are interesting and fabulous—but you’re going to be disappointed by him.”

“Hmmm.” He drew an eight on my thigh with his middle finger. An infinity sign. “By ‘special,’ do you mean slow?”

“By ‘special,’ I mean special,” I said, gingerly removing his hand. Here I was trying to tell him about Bernie, and he was trying to get in my pants! “The girl is more like you. She’s into books. She’s really smart. But you pay more attention to your son, I guess because he’s a boy. You want to force him to be like you, even though he isn’t.”

“Have I told you today how beautiful you are?”

“What would you do if you knew in advance, I mean if you knew now, that something terrible was going to happen after you left your family? Hypothetically speaking.”

A big part of me blamed my dad for what happened to Bernie. He used to shake him. He used to whip Bernie with his belt when he got things wrong. He used to drill him, night after night. It was important that I be smart, I thought. It was important to compensate for Bernie’s failings. I was the good child. I was an outstanding student, but it didn’t matter how much I excelled. I was my brother’s afterbirth. I was invisible. I was the girl.

“I’d rather not speak hypothetically. Let’s be direct. Don’t you think it’s time we take our relationship to the next level?”

I wanted to hurt him for hurting Bernie, and I wanted to shock him into seeing me.

“Your son dies in a freak accident.”

“Quit playing around.”

“Of a broken heart.” I was getting ahead of myself and treading dangerous water, but I didn’t know how to stop. My words tumbled out. “He electrocuted himself because he couldn’t bear the thought that he was a disappointment to you.”

“That’s enough,” my father said. “Let’s make out.”

I realized how ridiculous I sounded. My brother died a preposterous death. I had to revise events in order to be believed, and I had to get my tenses right. “No. He’ll be in a train wreck.”

This was close to the truth, though Bernie, not the train, was the wreck. Everyone knows better than to touch the third rail of the tracks. Bernie knew better too, even if he was impaired, even if he was drunk when he climbed to the roof of the Dinky train, even if he was off balance, even if he was only an angry teenager acting out to regain our father’s attention.

“Well, which is it? Broken heart, electrocution, or train wreck?” my father sneered, reaching for my breasts. I swatted away his hand.

They had to amputate his left hand. The current that shot through him was so strong it short-circuited his brain. It fried him inside out. His skin, which was slightly darker than mine, was so badly burned it no longer resembled skin. It was leather. It was the texture of the Rocky Mountains on my relief map of the United States. He didn’t belong to a race. He didn’t belong to this world. But then again, he wasn’t dead.

“Bernie was in a coma,” I blurted.

“Sounds like a soap opera,” my father said. He wasn’t wrong. Clearly, I was trying his patience.

“You have to promise me something,” I said, desperate for strategy. If I couldn’t count on him to fix things, then I was going to have to do it myself. “You have to give me something.”

“What are you talking about, sweetheart?”

I had no idea what I was talking about.

“I want you to give me this.” I pulled the feather out of The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. It was a talisman. It was a quill for rewriting the future. I believed my father had to give it to me in order for it to be effective. I couldn’t just tuck it under my shirt and steal it from him while he wasn’t looking. He had to want me to have it.

“Okay. It’s yours,” my father said. He casually took off his glasses and cleaned the lenses on the hem of his undershirt, revealing a patch of tightly curled hairs on his navel.

“Really?”

“Yes. On one condition.” He paused. “You have to give me something in return.”

“What do you want?”

“You know,” he said suggestively.

“Oh, that.” I looked away from his stomach.

“Come here, little girl,” he drawled, pulling me onto his lap. Then, as if he hadn’t heard a single word I’d said, he drew the feather from my hand and used its tip to tickle my right nipple through the cotton of my T-shirt.

I chewed on the knuckle of my thumb, which is what my mother does when she balances her checkbook.

“Don’t be scared,” my father said. He placed his mouth delicately on the topmost knob of my spine and sucked.

An explosion sounded from the east, and the sky brightened in a sheet of color. I leaped off his lap and leaned over the balcony railing, craning my head in the direction of the noise. It was a welcome distraction. The fireworks sizzled, but we weren’t high enough to see them.

Fifteen years from then, I would be five. I would be sitting on my father’s shoulders under a shower of light. I would remember it only because my mother took that picture with him idly holding one of my ankles. It is the photograph I remember. It is the picture of what my mother saw in my face as I watched the fireworks from those dizzying heights.

I didn’t want those pyrotechnics refracted through somebody else’s memory. I wanted to see them firsthand. Just over there, just beyond the hospital, just down the road, bouquet after bouquet, those pasqueflowers were showing Milwaukeetheir hearts.

“Let’s go to the lake!” I begged.

“You’re embarrassing me, Lynn.”

I felt him withdrawing. It was a feeling I knew, and it filled me with panic.

“Promise,” I pleaded. “Promise you’ll never leave me.”

My father shook his head and smirked. “Come here.” He circled my waist in his red-brown arms, which were Bernie’s arms. He pulled me against him. “You are one weird girl.” I started to cry into his chest then, either because he was patronizing me or because the smell of him was too much. He cradled my head between his palms and wiped away my tears with his thumbs. “Don’t cry,” he said. “That’s why I love you.”

I removed my father’s glasses to be sure that he could see me.

Before I knew what was happening, he kissed me. His full lips were soft and eager. He pushed his tongue into my mouth. I closed my eyes and inhaled his breath. I felt the sandpaper of my father’s stubble against my cheek. Through the earmuffs of his palms, the fireworks roared. I didn’t resist. I let him kiss me, and I kissed him back, melting into his mouth. He tasted of his pipe. I suppose I tasted of his soy sauce. Our kiss revolved, lengthened, firmed. My nipples hardened. My heart was a rabbit. I felt the muscles of his stomach against my ribs and his hands gripping my ass. He rocked me back and forth. I was the woman in his arms being wanted.

I was my mother.

His groin hardened against me. He ground it into my thigh. I felt it. I felt it. The sick hard proof of my father’s love.

A string of firecrackers seemed to detonate in my inner ear. I pulled away from him then, overtaken by shame. “Stop,” I panted.

“Shhh,” he whispered, unbuckling his belt.

“No, stop!”

“What’s wrong?” he asked, reaching for me. “Don’t be scared, little girl.”

All he wanted was to screw me. Her. I had plagiarized my mother, and it was more than possible I had recklessly upset the metaphysical balance of things. “I have to go,” I insisted, struggling to detach myself from his embrace.

“No, you don’t,” he purred, strengthening his grip around my waist. “Quit playing hard to get.”

“Please stop.” I recoiled. I felt sick. “Someone will see.”

“Nobody’s watching,” he said, darkly. And he was right. He pinned me against the sliding glass door, undid the button of my jeans, slid his hand beneath the waistband of my underwear, and gripped my vulva.

“I knew it,” he said. I was wet.

My father pressed against me. I bit him then, on the cheekbone, much harder than I needed to. Hard enough to leave teeth marks. He touched that beautiful double horseshoe, that marvel of orthodontia. We were both surprised. His eyes were bright and wide. “What was that for?” he asked.

I suspected that he liked it.

Truly, I bit him for trumping me with his race and his cock, for rehearsing his own greatness yet revealing next to nothing of himself. I bit him for his self-importance, for his refusal to listen, for his lack of generosity, and for his inability to appreciate my mother. I bit him for seeing her as interchangeable, for neglecting to notice that my eyes were brown, and for being too cowardly to visit Bernie after the accident. I bit him in self-defense. But what I said was, “That’s for not asking me anything about my bubbles!”

In my clumsy effort to get away, I overturned the apple crate, upsetting his bag of loose tobacco. I left him there, to sweep up the leaves and wonder. “Lynn!” he called after me as I crashed down the stairs, away from him and back to my life. He called my mother’s name again over the balcony and into the night. Lynn! Back then he didn’t want to lose her.

IV

On the short trip back to the hospital, I thought, impractically, of bubbles.

I remembered Bernie up on the roof of the back porch, churning a plastic wand the length of his forearm in a bucketful of soapy water. He wore a bath towel as a makeshift cape. I am down in the backyard gazing up at him. I am the magician’s assistant, shading my eyes. My brother is the sun. The wand in his hand is attached to a red canvas strap. When my brother lifts the wand from the bucket and waves it in the air, the strap curves out like the letter D and a film of soap blows out to form an enormous bubble. To my delight, he does this again and again. How short, the lifespan of bubbles! They float down to me like rainbows: impossible bubbles, bubbles the size of basketballs, iridescent as oil slicks on a wet road.

(This too I remember because of a photograph taken by my mother.)

“Catch!” Bernie cries. “Catch them if you can!” I chase after those distorted spheres, clapping between my little hands the ones that don’t float over the fence or self-destruct in the branches of the dogwood tree.

Back on the fourth floor of Aurora Sinai Medical Center, the priest had come and gone. The oil marks of extreme unction graced my grandmother’s forehead and hands. Olivia Lenore! She had shrunk into the white envelope of the hospital sheets, her mouth a rictus of silver fillings, her high forehead the same as her daughters’ and mine, her eyes milky and unseeing. Aunt Patty was moaning at the foot of the bed, “She never loved us! Never! She loved that drunk skunk more than she ever loved us!”

Patty was referring to my Pops. He used to drink Jim Beam like it was juice, and when that was gone he’d polish off the crème de menthe or the rubbing alcohol and abuse her. I knew about this because my mother told me. It was never a secret. She talked about that kind of thing while helping me make clothes for my paper doll, a figure she cut out of a brown paper ShopRite bag to look like me. “Here are some glittery genie pants for Space Girl,” she’d say in one breath. And in the next, “Your Aunt Patty used to put food on the table when your Pops was drying out in the drunk tank. Usually it was a tuna casserole. Now let’s make Space Girl a bathing suit for the lakes of Jupiter.”

“Shhh,” my mother rocked her older sister, stroking her back with great patience, over and over again. What else is a sibling for but this—to comfort us in the face of our parents’ miserable failings? “Shhh,” she coached. “It’s all right. It’s over.”

My mother noticed me in the doorway, and I noticed her. She was slouching. So was I. Under her heavy eyebrows, she wore a look of surprise.

She hadn’t been loved as she deserved. Not by my father, and not by me.

“I’m sorry,” I said. I held a bouquet of refrigerated chrysanthemums in my hands. It was all my ten dollars could buy from the fresh-flower vending machine on the first floor. Because there weren’t any free surfaces in that close, depressing little room, I lay the bouquet on Grammy Livy’s concave chest.

“She never loved us!” My aunt bawled like a twelve-year-old child.

“Shhh, Patty. She did. You know she did. It’s all right.”

“I’m sorry I wasn’t here,” I offered.

“You’re here now. Your Grammy told me to tell you she loved you.”

“No, she didn’t!” cried my aunt. “She loved no one but our father—the foolish, foolish woman.”

“Shhh, Patty. Emma. Your Grammy wanted to give you something. Look inthere.” She pointed her double chin at the drawer in the narrow particleboard table at the side of my grandmother’s deathbed.

“It was her job to protect us! She failed us miserably!”

“What is it?” I asked.

“Look and see.”

There were two books in the drawer. One was my grandmother’s Bible. The other was her dictionary.

“She wanted you to have it,” my mother lied.

“She didn’t love us! Why didn’t she love us?”

“You know she did,” my mother gently scolded. “She loved us the best she could.”

I picked up the dictionary. It was good and solid and heavy as a baby. How did she know? How did my mother know this was the exact right thing?

“Well, aren’t you two as pleased as punch,” said Patty. “How come the kid gets restitution? Where’s my restitution?” My aunt looked me up and down. Her eyes were bloodshot, and her voice was gravel. “Your shirt’s dirty,” she said.

I hugged the dictionary to my chest to hide the soy sauce stain.

“Where the heck have you been?” Aunt Patty asked.

“It’s Independence Day,” I said.

“So?”

“I went for a walk.”

“Yeah, well. A walk.” Aunt Patty knuckled her eyes. “A walk would be nice. A walk sounds like just the right thing right about now. Where are my shoes? If you’ll excuse me, ladies”—she bowed toward Grammy—“your highness. I’ve decided to go on a little walk myself.” She slipped on her shoes, picked up her purse, applied some lipstick, snatched the chrysanthemums, and left.

“She’s going to a bar,” I said.

“That’s true.”

I wasn’t sure what was supposed to happen next. I felt shy in my mother’s company.

“Mom?”

“Yes, bug?”

“What do we do now?”

“We just sit with her body for a while and wait.”

I observed my grandmother’s body in the lamplight. The fingers were gnarled stiff with arthritis, their fingertips yellowed with nicotine.

Then I studied my mother. Her front tooth was chipped where Bernie dinged her with his baby rattle. Her breasts were sagging. The veins showed in her hands, and there was an absence where her wedding band used to be. Here we were at last, I thought, without the men in our lives to distract us. “I really miss Bernie,” I said.

“Me too.” She fingered the cross around her neck and patted the space next to her at the foot of the bed. I joined her there but avoided looking at my grandmother’s corpse. It was a reminder that I would lose my mother too.

“I used to think he was the only person in the world who looked like me,” I confessed.

My mother would have gone on caring for Bernie forever. That’s the sort of person she was—slavish, I used to think. A saint. But to me, that lifeless, brain-deadform was not my brother, and I couldn’t stand to keep watching her wipe away its drool and bathe between its legs with a sponge as if magically it could hear her singing to him. She didn’t know what I had done to end it.

“You’re both beautiful,” my mother said.

“I know,” I said, “but I also look a lot like you.”

“Well, of course you do,” she smiled. “I spent five hours on my back pushing you out, didn’t I?”

“I guess so,” I said. “But I’m not good like you are.”

“Don’t be melodramatic.”

“I’m not. I don’t even feel bad about Grammy Livy.”

“That’s because she was old. She was seventy-seven. She was supposed to die. Your brother, on the other hand . . .”

We waited. We waited for minutes that ticked into decades. I couldn’t bear that awful silence. I didn’t have the grammar for it.

“Mom?”

“Yes, Emma?”

I wanted to woo her. I wanted to toast her.

“What was your thesis called?” I asked. Had I been older or wiser I might have posed it another way. I might have asked her how we earn grace.

“Oh, that was so long ago,” she said. “I don’t remember.”

“Yes, you do,” I pressed.

Dedicated to my Uncle Bill Murtaugh, in Milwaukee, for telling me how my parents met.

Emily Raboteau is the author of The Professor's Daughter and Searching for Zion, winner of a 2014 American Book Award and a finalist for the Hurston Wright Award. She is currently Distinguished Faculty in the CUNY Graduate Center's Advanced Research Collaborative, where she's completing her third book.