Phone Interview with Ricardo Dominguez and Amy Sara Carroll regarding Sustenance: A Play for All Trans [ ] Borders (chapbook/pamphlet), Electronic Disturbance Theatre/b.a.n.g. lab, New York: Printed Matter, Inc. (Artists & Activists series), 2010.

click on image to view PDF

(click here to download, right click and

open in new tab if having difficulties)

Sustenance: A Play for All Trans [ ] Borders, a collaborative work by Ricardo Dominguez and Amy Sara Carroll functions not solely as a play in its performative aspects but also a brilliant artistic and activist endeavor. Through Sustenance, Dominguez and Carroll along with their collaborators challenge both the way in which technology, humanitarianism, borders, poetry, and politics are represented and information is dispersed. Through their work in Sustenance they are able to undermine politics of publication and censorship in their efforts to change the way information is made accessible to both those attempting to survive and those helping others survive. Sustenance is a chapbook/pamphlet set within a play that both describes and defines the Transborder Immigrant Tool and at the same time provides the story/stories that it falls within in and is making. A vital aspect of this play is the weaving of narratives to tell a living story that is still in the process of being written and told. It was a great honor to have the opportunity to be able to interview Ricardo Dominguez and Amy Sara Carroll via telephone on Sunday, June 12, 2011.

ENRIQUEZ-LOYA: At the beginning of the pamphlet play, you say “our project represents a conversation piece, a reminder that people are dying, an ethical intervention, a hand extended to those who are lost and dehydrated.”My question is, what do you imagine/hope will happen with this work? Could you speak about the reception you anticipate or have received, by would-be crossers? And how can such a technology be widely distributed to those that most need these services?

DOMINGUEZ: We imagine the Transborder Immigrant Tool (TBT) as a three stage project: the first part focused on assembling a conceptual gesture that could disturb the political aesthetics of the current Mexico/U.S. border and bring attention the immigrant deaths that it has caused. The second involved finding a ubiquitous technology that could amplify the issue; we are new media artists, after all. And, the third stage, not fully realized, would be to distribute TBT on multiple levels as art, as sharable code, and as working tool. In 2007 Brett Stalbaum and I, who cofounded Electronic Disturbance Theater in the 90’s and established electronic civil disobedience as both a theory and a practice, specifically in relation to supporting the Zapatistas in Chiapas, Mexico, were sitting around at UCSD, trying to relocate, or dislocate, what is traditionally named in new media art as locative media, where artists use GPS, global positioning system software, to create new forms of art. Brett has been involved in thinking about locative media since 2000 when global positioning technology was made available to the civic part of the world, after the military released it, and one of the things that locative media has particularly focused on, in terms of its aesthetics, has been predominately to look at urban spaces and develop narratives around those spaces. That is, it could be a narrative about a historical event that happened on the street, or it could be a fictional narrative, but it has been an urban-based aesthetics.

Brett Stalbaum and his partner, artist Paula Poole, were very interested in non-urban locative media. They developed a gesture called the “virtual hiker,” a GPS system that would allow them to basically walk in extremely dangerous territory in the southwestern US and allow this artificial algorithm to prefabricate what type of walks they would take. And this was particularly interesting to me because both of them, while deeply immersed in nature, really do not have a very strong sense of direction. So it makes sense that they would develop this kind of virtual hiker to help them do the things they love, and also orient them at the same time. I have never been particularly interested in the work that locative media had been doing. But I found Brett’s and Paula’s walking tool, in terms of the dangerous desert terrain, really quite interesting. So in 2007, I began to have a conversation with Brett about how we could take this project and anchor it to the questions that we found ourselves asking about the environment of the San Diego/Tijuana border, because we’re both teaching at University of California San Diego. And of course, we both knew that one of the outcomes of “Operation Gatekeeper” in 1994 was this extremely dangerous trek, what is called “The Devil’s Highway” (in Arizona) as a space where people are dying of dehydration. And we also knew that there were NGO’s, like No More Deaths, Water Station Inc. and Border Angels, who are working extremely hard to leave water out in the borderlands. Out of that conversation, we developed the idea of the Transborder Immigrant Tool that would speak to the use of a locative media. We sought to dislocate urban space in the service of creating a gesture that would somehow allow the navigation of the borderlands to find water. And so in 2007, I wrote a proposal for the Transborder Immigrant Tool.

And the other element that is important for Electronic Disturbance Theater was that, not only would we take a new media aesthetic like locative media and would reconceptualize it around the issues of the border, but Electronic Disturbance Theater was always deeply attached to the notion of the poetic. We believed that poetry should be deeply involved in the core manifestation of the gesture. We always approached electronic civil disobedience gestures as poetic interventions aggregated around virtual sit-ins. For instance, we also created another tool that we used at the Border Hack festival in 2000, called the Zapatista Tribal Port Scan, where we uploaded into the U.S. Border Patrol servers a series of poems. And so when I wrote the proposal for the Transborder Immigrant Tool to try to find funding at my institution, the University of California San Diego, poetry became part of the proposal. In 2007, we did receive funding for both of those elements from different components at the university.

ENRIQUEZ-LOYA: Could you speak perhaps about the type of reception that you anticipate or have received from would-be crossers, or how we can distribute these, not necessarily in a theoretical format, but how we can actually get these devices to them, the TBT’s?

DOMINGUEZ: The proposal for TBT was utopian in terms of the timeline we had put together, namely it was unrealistic to think that the project’s development would take only one year to complete. The number one question was what sort of cell phones were available that could be reconfigured towards other ends? Answering that question actually took a little while, but we finally found an iMotorola series that is inexpensive, has a GPS enabled system, and was reconfigurable in terms of the interface and ability to contain some amount of poetry. So once we had that, we began to reexamine its cognitive design, and we were very lucky to have a neuro-cognitive undergraduate, Jason Navarro, work with us and begin to think about possible ways the phone might work in the hands of an end-user. For instance, because the phone’s screen is small and a potential user might be disoriented, we started to think in terms of water-dousing, the tradition of using a stick to find water. So the phone would vibrate to a voice request for ‘agua’ or ‘water.’ The vibration would get stronger the closer you were to a water cache. And then the other thing that happened was that Amy joined us in 2008, and began to think about the poetry and how that poetry would work. And she’ll speak more eloquently to that.

In terms of distribution, the TBT code is available, and has been available for some time, on a site called walkingtools.net. The next stage would be to have a series of workshops with people at Casas del Migrante and other NGOs that are dealing with potential immigrants. And there, we imagined that there would be a conversation about design where we would stress that TBT was only a last-mile safety tool. Then as we were preparing to move in that direction we came under investigation, spearheaded by three Republican Congressmen from San Diego, and then my own university system, UCSD. B.a.n.g. lab, the laboratory I run at CALIT2, came under investigation as well, and then the FBI Cyber Division started investigating me. So basically, by the end of 2009/2010, the project really had to come to a halt because of these investigations, because we needed to procure legal counsel, and because UCSD began to try to de-tenure me. Our legal counsel said that we shouldn’t move toward the second stage of bringing it to the immigrant community until these investigations were resolved. And so, this didn’t really happen until the end of 2010, and the FBI investigation ended around November 2010. All this really slowed us down.

In the near future, we still hope to have conversations with the NGOs, churches, community groups in Tijuana about their particular interests in TBT. So at this time we haven’t handed the tool over to the immigrant populations who may or may not cross the border. But, the code has been distributed, and it is available. And at this point, we are at the stage where we are trying to think about moving onto the next level. And on June 4th, 2011, as part of Political Equator 3, a large public culture project by Teddy Cruz, a professor at UCSD, we took TBT through an aqueduct into Tijuana as our first gesture of bringing the project to Mexico. Symbolic, this gesture nevertheless activates the next path of the tool.

ENRIQUEZ-LOYA: I’m curious of your choice for the distribution of this information through this pamphlet, play, over other forms of communication. For example, I loved that there is so much beautiful work imbedded in so few pages. There are even multiple languages, which is not only significant, I imagine, but also perfect for the task. My question is what was the motivation for creating the pamphlet in this format?

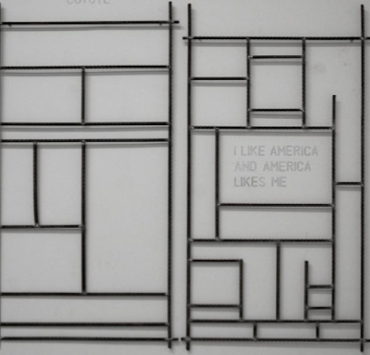

CARROLL: We’ve actually distributed information and the poems in various formats. In fact, Vandal was the first place that published one of the poems I wrote for TBT. But for this particular pamphlet, we were invited by Printed Matter Inc. to create something for their “Artists & Activists” series. They sent us previous pamphlets within the series, gave us a page length, and said “if you can get it to us in two weeks…” And so I started working on trying to figure out how to organize our various voices, because there are five of us—me, Ricardo, Brett Stalbaum, Elle Mehrmand, and Micha Cárdenas. Moreover, the pamphlet actually includes not only our five voices but the work of certain people that we’d invited to translate poems too. Ricardo initially had the idea of a play, and then I had the idea that I wanted there to be an overload in the text, keeping in mind that Printed Matter Inc. planned to distribute the pamphlet in and to art communities. I did the layout of Sustenance because I wanted the poems to be on the sides, in boxes of conversation. I also was really interested in repurposing the hate-speech and death-threats that we had received as kind of alternate, naturalized aesthetics. And that included the letter by the congressional representatives, calling for an investigation of our work. The Congressmen did not send us that letter and our universities did not share it with us. Rather, a journalist forwarded the letter as a PDF to Ricardo. So it was purely by accident that it fell into our hands, and I’m not sure how the journalist ran across it to begin with. But we suddenly were informed we were under investigation, but we hadn’t actually seen that letter.

In other words, some of the formal gestures of the pamphlet are distinct from other writing modes that we have used to make the project accessible. Those latter modes include: we were invited by the San Diego Union Tribune to write a really brief editorial that would be published alongside an editorial written by Duncan Hunter (who is one of the congressional representatives who had called for the investigation of the work), critiquing TBT. We didn’t intersperse poems in the same way in that letter. We also didn’t attempt any reversion to an idea that we should reach as many people as possible. In fact, we were really interested in what I call a “translucent” writing style. We don’t necessarily want to promote a style that’s completely transparent, nor are we interested in something that’s completely opaque. In contrast to the neoliberal moment/s we’re all living that advocate complete transparency while obscuring their own opacities, we wanted to navigate an in between in both the pamphlets and in other spaces, like things we’ve had to write for the editorial or our installation included in the California Biennial. I had to write a project statement for that (besides writing the poetry included on the phones) and again I aimed for a translucent effect (one that balanced its transparencies and opacities) . In Sustenance, I tried to piece together our five voices and different writing styles, and those of others, our different lived experiences and expertise that we bring to the project together. I did not go for some completely neatly-packaged, unified whole, but rather something that would reflect our own glorious multi-vocality. Moreover, I didn’t want there to be any lines between what might be a more academic or critical prose and the poetry of the pamphlet. In fact, I wanted people to look at Sustenance and think “well which part is actually the poetry? And why is the poetry like this? Why is it this way? And why are these death threats here!—do they mean to imply that those are poetry too?” Mainly, I wanted people to ponder about the aesthetics of hate speech; because, nobody talks about Fox News’s aesthetics.

ENRIQUEZ-LOYA: This project as a pamphlet/play is really doing so much great work in such a small space, kind of what we’ve been talking about. I was thinking of the performative aspects of the TBT as a practice of humanitarian aid, for example, and the response call-to-action you hope to invoke in your readers with this pamphlet/play?

CARROLL: Right. So, again for this particular pamphlet, we knew that the audience was going to be primarily artistic communities. And so, for us, one of the questions was: how can we reach our audience in a way that wouldn’t involve an immediate dismissal of the work? I’m not sure if the pamphlet was a successful gamble or not. But, of course, I also envisioned Sustenance as potentially having a more general distribution. I teach in Latin@ Studies at the University of Michigan and I routinely offer a survey course of contemporary Latin@ Literature, so I suppose a part of me hoped it might be taught in “creative writing” classes or surveys of “Latin@ Lit” that would complicate what equals each.

I should also note that we performed the pamphlet. The Galería de la Raza in San Francisco invited us to do a reading of it in June 2010. So we presented the pamphlet, but that’s actually the only place where we’ve ever read aloud the entire piece. La Galería also invited us to do a billboard in September 2010. They have a billboard series, so if you went to their website you could find the one we did (http://www.galeriadelaraza.org/eng/events/index.php?op=view&id=2418). The billboard was comprised of an image that I had taken in the desert. For some time, I have been creating/writing concrete poetry and that billboard reflects some of my longstanding interests migrating into TBT.

I should note too that part of the reason that we were invited, almost randomly, by Printed Matter, Inc. to do this pamphlet is because there had been this massive viral media coverage of the project. The majority of that coverage had and has been this really extreme representation of the project, and how irresponsible we were in working on a project that people, some newspapers, some television stations, were characterizing as a federal felony. A.A. Bronson (the artist who founded Printed Matter, Inc.) heard about the project because lots of people were hearing about the project. But he liked the project, he found it interesting, so he invited us to do this. But one thing I thought a lot about is that this is also where I became certain that my prior ruminations on this question of a translucent aesthetic were on target. Because it seemed to me that the news coverage was always trying to promote its representation of the project as ‘fact-checking’ and ‘transparent representation.’ And I thought nothing I’ve heard about TBT is transparent! In fact, the opacities in the project’s coverage made me think even more about dehumanizations inherent in representations of people crossing the border. So course we always reasoned, “If I were in the desert, I would want water and, of course, I would choose water over a poem. But what if we also made it a point to resist the dehumanization of human beings and to suggest the aesthetic also sustains, and that the assumptions that go along with certain kinds of representations of the undocumented is always that they wouldn’t have any interest in poetry?” Concomitantly, it puzzles me that the default assumption for the general viewer of television or reader of newspaper is always that of a dumbed down subjectivity. There’s no possibility of imagining that someone, that the general public, would be interested in reading about a conceptual gesture or an investment in intercepting language and repurposing it. We began to reflect: we had thought that the distribution of the project was getting it into the hands of people that are crossing. But what if there are other modes of distribution, i.e., just the thought of this project, not its deployment, intercedes in contemporary discourses about immigration, about undocumented entrance, about shifting demographics of the United States and the continent?

ENRIQUEZ-LOYA: At one moment you discuss the availability of GPS devices at Wal-Mart and Best Buy in Mexico, and you note that “capitalism long ago accomplished what the activists, right, and neo-liberal administrations fear most.” This is a wonderful moment that I think speaks volume about so many of the debates surrounding immigration, the border, and so forth. So my question is: what effect does your research have on these debates? Or how do you feel that your work will challenge the border as a real and still-contested space?

CARROLL: I don’t know. It’s very hard to gauge when you’re in the middle of a project what effect the research is actually going to have on the debate. So I am not certain how to answer your question. I mean maybe in our own small spheres of influence we’ll have an effect. I don’t think any of us believe that the project is going to have a huge national effect. The particular passage of the pamphlet you highlight actually was written by Brett, who has done the code for TBT. I love that passage also. And I think in terms of the work ‘challenging’ and ‘problematizing the border,’ all of us—and we’ve talked extensively as collaborators—I think all of us have wanted to challenge and problematize the border’s status what Mary Pat Brady calls, “a state-sponsored aesthetic project.” We prefer think about the border in terms of Edward Said’s distinction between real and imaginary geographies.

DOMINGUEZ: Well I run a laboratory at CALIT2, California Information Technology 2, and the laboratory is called b.a.n.g. lab. And when I established the lab in 2004, there were three areas of research that would be at the core: one electronic civil disobedience and hacktivism; two, border disturbance art; and finally, interventions into nano-technology and establishing nano-poetics. So it was apparent to me, never having lived at the San Diego/Tijuana border, that by choosing border disturbance art/technologies as an arena of investigation for artist research, it would take into account this long history of the border as an aesthetic project. From the work of, say, Guillermomo Gómez-Peña to that of the BAW/TAF, to that of Louis Hock, artists themselves have consistently searched to disturb that condition of the border. So I think that the history of art practices in problematizing the border as both a very real and dangerous thing, and as a contested space, but also as an art space. And that probably is the most difficult element for people to be cognizant of, while problematizing the border and the contested elements of the border are certainly well-discussed and a priority of the dialogue, the question of it as an art space, as an aesthetic space has certainly not been involved in the dialogue in a wider way. So at least for me, an important element of this question is that we do have to look at the border as a space for performance. Artists, through their practices, are thinking about the border as a dislocated space for the manifestation of what I would call ‘trans-citizenship.’ And so with the other question about “capitalism long ago accomplished what the activists, right, and neo-liberal administrations fear most” is indeed something that has been reiterated and brought to the foreground by the Transborder Immigrant Tool (I hope). That is, if indeed people are viewing this as a traitorous application, then one would have to view the entire GPS structure that is available for purchase at Wal-Mart and Best Buy anywhere in Mexico or anywhere in the global South, that is moving into the North, as traitorous. So indeed, if the nation-state and corporations and the fringe of the right-wing are concerned about the Transborder Immigrant Tool, they should be ultimately concerned about NAFTA, about neo-liberalism and globalization, and the U.S.’s long-historical attachment to manifest destiny.

ENRIQUEZ-LOYA: Wonderful. I’m very excited about this project and thinking of all the ways I can use this as a teaching device for rhetoric classes.

DOMINGUEZ: Brett Stalbaum and I are professors in the Visual Arts Department at UCSD. And we run what is called ICAM, Internet Computing Art and Media, undergraduate program. And so part of our work is to offer these sorts of new media art gestures as pedagogical tools for these undergraduates to begin to think conceptually about what code can do in establishing and speaking to new forms of aesthetics that are no longer attached just to questions of “What can I do with my Xbox?” But really thinking about a wider history of conceptual art, social intervention, as well as the development of code (or not about code itself, but about what it can accomplish in terms of aesthetic and conceptual history). So that’s just a side note in terms of pedagogy, that’s also important to us.

ENRIQUEZ-LOYA: It is. Actually, the idea that there’s a wider social aspect to it ties into my next question: Citing Thoreau when he says “let your life be a counter-fiction to stop the machine.” And then later, Rancière is saying “the real must be fictionalized in order to be thought.” You end the question with “Plagiarize Utopia. Let your life be counter-fiction to stop the machine.” For me, obviously, this is absolutely perfect. I ask: what do you imagine as a machine, and how can our lives be counter-fiction? And how does your work with the TBT’s in this pamphlet/play fit within this cultural action?

DOMINGUEZ: The structure of our conceptual work with Electronic Disturbance Theater, 1.0 and 2.0, was to establish the idea and practice of electronic civil disobedience. And certainly we’re aware that civil disobedience by Henry David Thoreau marked in the temporal way as a gesture against the US/Mexican border of 1848, and his belief that the US/Mexican war was an expansion of the slave economy. And so inherent in ideas is this notion that Thoreau put forth about using civil disobedience as a space to disturb, block, and trespass the machine that allows the expansion of the many-layered histories of slave economies. Much of the work that we do at the b.a.n.g. lab (bang.calit2.net) is to begin a politics of rehearsal, a rehearsal of politics, as part of our art practice. A type of science of the oppressed or engineering of the oppressed that imagines creating speculations that automatically, conceptually, begin to disturb the lines of thinking that crisscross not only our bodies, but the ecologies of the Americas, and certainly the globe. Can we think about globalization as borderization? And so it becomes necessary to create these speculative disturbances that can allow one to think about another possibility, another impossibility, that these systems both manifest and, at the same time, call for an “anti-anti-utopian” potentiality, so that the engineering of the oppressed, the science of the oppressed, is about rehearsing the fictions that will then become realities. And then this element of plagiarizing Utopia…again, it’s around the notion that immigrant culture creates a ‘trans’ of citizenship. Since immigrants across the globe, minute by minute, are probably the largest nation-state on the planet, can this kind of friction of the machine anti-flow grouping of community create a space where Utopia is being manifested, and our work is just simply plagiarizing, cut-and-pasting what is already an assemblage or a system that is taking part by immigrants crossing at multiple spaces. And so the play itself, for me, is an attempt to create the multiple layers that manifest the friction, the speculative fictions, the rehearsal of politics, of a counter-machine–a machine of difference that can only really be performed by more than the multitude, if you will.

ENRIQUEZ-LOYA: In your pamphlet, you include a series of blatantly hateful emails from individuals rather unhappy with your research. Why did you choose to include them in your pamphlet/play? What effect do their physical presence (as real emails) and their voices have on your work and on the reception of your work? Also, on the other side of the spectrum, I’m curious about the support you’ve received from the community. Has the community being particularly supportive?

DOMINGUEZ: Well, we wanted to use the emails in the text to point towards a space of reflection between excitable speech, inherent violence, and it’s very targeted submitting of who is allowed to speak. The emails were really focused on who would be allowed to speak. That is, queers aren’t allowed to speak. Women aren’t allowed to speak. Brown people aren’t allowed to speak. And, queer, brown women really “need to shut the fuck up!” White people who enter into coalition with these communities aren’t allowed to speak. And if one does speak and create gestures that manifest this counter-space, then the cultural targeting, the enactment of verbal violence is really unstoppable. And we certainly have not been the only individuals that have been in these crosshairs of, for lack of a better word, Fox-driven violence. So it was important to have that, and to contrast that particular excitable speech as Judith Butler, and certainly Amy, have thought about that, but to counter that with another performative agency, and that is “fearless speech.” And the pamphlet to a degree was hopefully this conversation between those two poles—in terms of what the line, meaning the line across the sand, in terms of the border, the line that crosses bodies—that one side of the line, when it does cross, is to enact fearless speech, to be able to take a measure of power. So the fearless speech has certainly called forth a great many communities that were receptive and were supportive of our work—certainly from academic communities, my own at UCSD, and art-based communities around new media and beyond. We’ve received letters of support locally. So I do think that the line in the sand really became clear to us, in terms of space, of violence. (in terms of those who do not want a certain community to speak, and when they do speak, to be shut down quickly as possible versus those communities who are extremely supportive of fearless speech, of crossing the line, and crossing that line in a manner that did not seek violence, but only the accounting of, and taking measure of that violence of that is created by Operation Gatekeeper and Fox News and what have you).

ENRIQUEZ-LOYA: I love that you include the written responses questioning your work, sources of funding, and such. First, why did you choose to include these in their entirety as opposed to briefly mentioning them occasionally? What role do they play? And second, how do you envision these entities responding to the fact that they are now part of a play? And that’s in regards to the PDF that the journalist sent you—the letter questioning your research, or the fact that you were under investigation.

DOMINGUEZ: Well, one of the crucial questions that I think our work, and particularly the research that b.a.n.g. lab does at CALIT2 was, when it was established, to enter into doing this research with the main goal being institutional critique. Because when I was invited to do my job talk and they said “what would be the focus and outcome of your lab’s research?” I said “Well, I certainly know what electronic civil disobedience and ‘hacktivism’ has done during the 90’s, in terms of the wider world. And I certainly do know the histories of border art in San Diego, California. But my research would be bound to this other forms of aesthetic and contemporary project or institutional critique, so that the gestures in terms of the research would be to measure the response of a university system, to measure the response of the public culture surrounding a gesture. And so the main reason for me of having that information, having those letters, having the information about the support, was—and is—so that individuals in communities and artists can see a direct infrastructure, if you will, that is being critiqued and that the critique is now fore-grounded, so it’s not an invisible element to the project, and in fact is an important quality of the project. So when I was brought before my committee to de-tenure me, it was this point, in terms of my job talk, that became important in allowing this project to go forth. That is, my research is focused on what manifestations of antagonisms or support a university has toward this type of work. I was given tenure based on the outcomes of this research. And I will continue to do this research because it was what I was hired to do. So it is important for me, as it is for Brett Stalbaum and everybody else, that the performative matrix of the Transborder Immigrant Tool be as clear as possible about where funding came from, what the response of the university system was, what the response of the larger California system was, and of course, what was the response of the nation-state, both in the US and in Mexico. That is, again to take a measure, an accounting, of those systems of power, versus what it does not want to be accounted for—that is the dying of the undocumented in this inhospitable space without sustenance, without hospitality.

ENRIQUEZ-LOYA: The next question actually ties partly to this. Although your work you’re doing with the TBT is incredibly rewarding, I can imagine that it might also be taxing on the personal life as well, considering the hate-mail and things of that sort. How do you consolidate the cost and benefits of your work? Do you see the negative responses you receive from non-supporters as further motivation to continue your work? How do you find the strength to continue in the face of this adversity?

DOMINGUEZ: On the most intimate level, the level of family, it was extremely difficult—that is that some of the violence would expand beyond email and begin to become more manifest and antagonism towards Amy and me and our son, Brett, Micha, Elle. We contacted the Department of Justice to make them aware of the connection between Fox News and the level of violence that we were getting. And certainly having to go through legal investigations, having to get lawyers, going through multiple investigations was difficult in terms of the psychological weight of that. But at the same time, especially for Brett and me, we had gone through similar encounters during the 90’s with the Department of Defense and the Mexican government. And so we had some sense that when one works in tactical media, when one functions at this level, that often power and its formations will be activated, and they will use whatever means they have to block you, to create such an emotional weight that one would refuse to move forward on whatever project one is working on. At the same time, as I keep repeating, part of the project is to take a measure of those systems of response, to allow those systems of response to make themselves manifest, so that one can then include them in the gestures and the work, so that communities and artists and activists in the wider public culture can become in-tune with both what one imagines would happen and what does happen. So both those things are sutured in, and ultimately, I think the strength that emerges from that is both a clearer sense of what the project means to all of us, and at the same time, a clearer sense of the institutions who seek to block it, what can’t be blocked, what can’t be stopped. They imagine this as a technical system, as a global positioning system, that can be turned off, blocked, or defunded, as opposed to a geo-poetic system, which functions otherwise, that moves in an alter-possibility. And so it can’t be shut down even if they decide that they no longer want to participate as an institution. And I think, to me, that’s one of the forces and power behind Amy’s poetry, is that it really allows this notion of the geo-poetic system to come to the foreground in a very powerful way, as a way to route around here and move us into another form of sustenance, a sustenance that the hospitality of language and a machine can accomplish.

ENRIQUEZ-LOYA: At the end of your pamphlet, you say, “Becoming Fugitive [‘Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?’], an audible postscript [from off stage left]: The trans in transborder and transgender can signify a crossing, but also a hope and a bravery in crossing. As a trans person, I am familiar with the hope of crossing.” I find it fascinating and fitting that you chose to quote Ellison here from Invisible Man especially because at this moment in the novel he is already underground and you preface this with “Becoming Fugitive.” What’s the role that you envision with Ellison in this project? Additionally, because this is an audible postscript from off stage, does this suggest in some way that we/the readers/audience are off stage? And/or what does it mean to be on stage? Furthermore, what’s the role of the transperson in relation to this literary reference?

CARROLL: A lot of this last portion was written by Micha, but I did write this stage direction. Micha and I had had a conversation about not reifying the ‘trans’ person in relationship to the project, but we wanted to think about and trouble the prefix ‘trans.’ And so I wanted her really important ideas about the ‘trans’ to function as a kind of critical post- script to the pamphlet (in the tradition of the Zapatista postscript that carries many a communiqué) , and I think that people often ask questions about “Well are you going to be able to pick up a signal in the desert?” and think about the project in terms of bandwidth, frequencies and reception. And I was very interested in emphasizing that sometimes projects become lower frequencies, and sometimes the metaphor of the lower frequencies might stand in for minority subjects in general, right? Those lines from Ellison have always been so important to me; they haunted me when I first read the novel. But also, the narrator of Invisible Man and the whole concept of an invisible man—the closing and the opening of the Invisible Man together, it’s someone who’s using the technologies at hand. He’s poaching off the lights at the beginning. And, then, there’s this idea of hibernation, possibility related to lower frequencies and the ways in which the novel troubles what might equal the political, what might equal activism, what might equal minority subjectivity. I view it as an invitation to the reader—to an audience who needs to come onstage, versus remain offstage. But, what does it mean to be onstage? Ellison’s question might not be an invitation to come onstage after all, but to realize that we’re already onstage.

I’ve thought a lot about Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s idea of the “privilege of unknowing” in this regard too, in relation to what we and others call the ‘humanitarian crisis’ on the US/Mexico border, but also on many borders: if you’re to look the other way and pretend like you don’t know about it—or not even pretend, but just not know about it—and cannot mull over a situation, there’s a privilege attached to that, right? So to me, the lower frequency is also about, just because you can’t see it or hear it, you think that means it’s not there? In general, when I talk about people giving me blank looks when I reference current violence in Mexico, I always tell myself again and again, “Start from a place of not assuming that a person is going to disagree or agree with you. Just tell people about things, because sometimes people just don’t know.” And sometimes the first time you tell someone something, they still don’t know. You have to say it again and again. And that, to me, is also the project of teaching in a classroom. Sometimes three years later, I’ll get an email from a student that goes something to the effect, “I never knew that your class was so important.” I think that when we’re trying to merge academics language and poetic language it was, I realized, often misrepresented and characterized as being particularly smug and didactic in the news coverage of the project. Fox News said it was didactic, and then I was showing someone I knew who had been an immigrant to the United States the project, and she didn’t view it as didactic at all. She started crying and told me that it was incredibly beautiful. And people having that response, and then within these news outlets it being represented as totally inaccessible and ridiculed, and “Who would ever want to read that poetry?” and “Who would ever want to think about the ideas in that way?” And so I was called upon to ponder the reception of our work. So we just put it out there and see who identifies or finds it interesting or who finds some points of connection or who doesn’t. You can’t really control that. When I was thinking about that, I thought maybe the question that I always believed Ellison was posing to me, the reader, maybe he was posing it to himself too as an author, to himself and his imagined coming communities. So it’s complicated to try to parse that single line, which could almost be a poem in-and-of itself. So, I reasoned, “Well, there’s got to be a way for us to imagine a poetics of confusion that would be actually productive, versus something that would be frustrating or anger-inducing.” This is a line for me that functions in that way. I understand it. I don’t probably understand it completely. But it’s really productively confusing for me.

The last part of the question I think is very important: “What’s the role of the ‘trans’ person in relation to this literary reference?” And I think the relationship is, again, one of a loose staging of that question “Who knows that that on the lower frequency doesn’t speak for you?” Because, you know, a lot of the hate mail that Micha received, or her experience of being in the world is often a misunderstanding to the point of anger at her person. I think that some of people’s anxiety about difference is also about, on some intuitive level, recognizing themselves in that lower frequency. A lot of these ideas were coming into play when we were thinking about quoting those lines.

Previously published in Vandaljournal, Insecurities

Chicana born and raised on the border between Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua Mexico and El Paso, Texas. Earned PhD in English with an emphasis on Cultural Rhetorics and Literatures of Color from Texas A&M University in 2012. Currently teaches courses in Composition, Cultural Rhetorics, Technical Writing, and Business & Professional Writing. Publications include, "The Calmécac Collective, or, How to Survive the Academic Industrial Complex through Radical Indigenous Practice." El Mundo Zurdo 3: Selected Works from the Meetings of the Society for the Study of Gloria Anzaldúa. Eds. Sonia Saldívar-Hull, Larissa Mercado-López, Antonia Castañeda. San Francisco: Aunt Lute (2013).