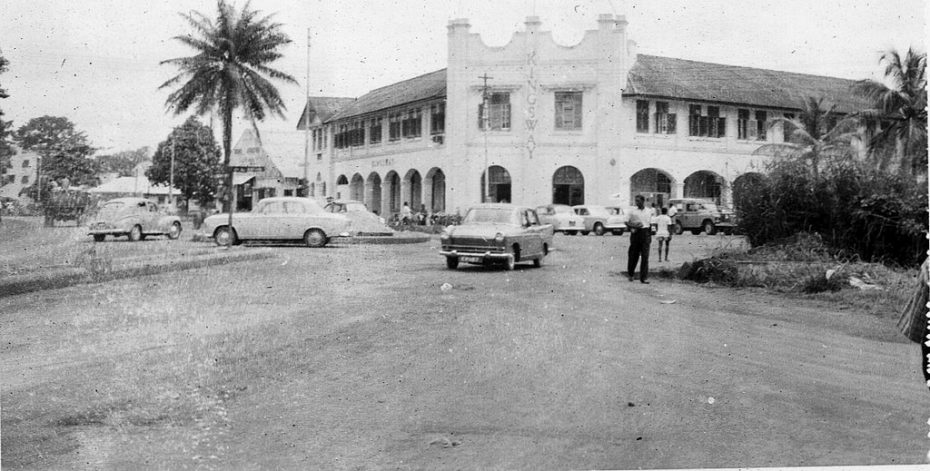

It was the summer of 2010 at the height of World Cup fever on an unusually slow afternoon at Festac Grill, a Nigerian restaurant sandwiched between an empty lot strewn with refuse and a car repair shop. This working-class Brooklyn neighborhood, whose streets were desolate at night, was busy during the day. At the repair shop, Black and brown men in blue overalls peered into hoods of cars and slid underneath them to poke at their bellies. A man and I were waiting for our takeout at the food counter in the dim restaurant. Its peach-colored walls were lined with haunting carved wood masks and canvasses drenched in vivid hues of blues, reds, and yellows. The aroma of goat meat pepper soup and ogbono thickened the air. Through tall black speakers sequestered in the corners of the oblong room, 9ice serenaded us with Mu Number. On one side of the room, mounted at the center of the wall, was a giant flat screen TV on which a soccer match was live: Senegal v USA. A few male patrons sat facing the screen with fingers poised in midair clasping soup-soaked balls of iyan.

“Ah ah! He should have scored, abi?” said one of them, dark like me.

The thin man beside me whose walnut brown face was all angles and stubble, wondered why our country, with all the skill we could boast of, was yet to take home the Cup. Our conversation began in pidgin, inflected with more and more Yoruba. Eventually, no longer capable of continuing the charade, I told him I didn’t speak the language.

Sometimes the exchange of hellos, of names, of places of birth would be enough to establish my Nigerian authenticity and bring these exchanges, these brief moments of recognition and connection, to a close. At other times, they were merely the ice-breaker; as people would launch into more complicated phrases, the singsong dialect pouring out of their mouths rapidly, my lack of fluency would become evident and my long-held shame would manifest a grim smile. I’m almost forty now, practically middle-aged, and still that grim smile is the best I can do when reminded of this cultural failing, this foreign-ness of my own native tongue.

“What do you mean you don’t speak Yoruba,” he asked, a shadow of pity darkening his face. “You should know how to speak your language. Didn’t your parents speak it at home?”

He raised an incredulous eyebrow and rested his hand on the counter. When I didn’t answer right away, he turned to face me and got a good look at the Yoruba and Edo kid who could barely carry on a conversation in either language. I did not know what to say to him: Do I say what I usually said, that, yes, my parents spoke multiple languages at home, but only to each other and not to us kids? That we were discouraged from speaking our languages? That we were discouraged from even speaking pidgin because, according to them, “that’s how bush people communicate”? Do I talk about how, despite spending the first fifteen years of my life in Nigeria, I barely knew the place? That during that time, when I wasn’t away at boarding school, I only ever saw the compounds of our homes, the interiors of our chauffeured cars? Do I tell him about the vice-like grip our parents, particularly my mom, had on us, and the paranoia undergirding it?

“No, I don’t speak Yoruba.”

The man shook his head, his pity looking more like sorrow. He grabbed his plastic bag – in which there were tupperwares containing fufu and egusi – off the counter and sauntered out of the restaurant. I looked at the woman at the cash register. Her ponytail was slowly coming undone and sweat beaded down her caramel forehead. Just beyond her was the kitchen where, through the glass panel of the door, I could see two older women in head ties, bent over the sink washing something. The cashier placed a bag of tupperware filled with my goodies on the countertop. I felt certain that she was silently judging me.

“$14.62 please?” she said.

Her eyes seemed to ask me the same questions the man had. I stared back for one second, trying to summon an unashamedness I did not feel. Failing, I lowered my gaze and fished money out of my pocket to pay her.

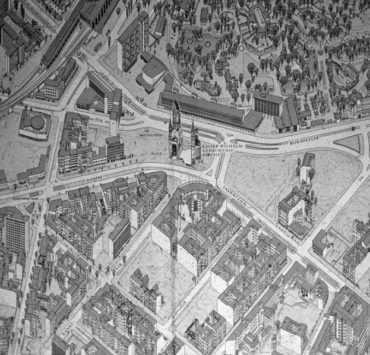

Yoruba, the language of my father’s people who are from the western region of Nigeria, is spoken by more than twenty-two million people within Nigeria and in other countries from Benin to Brazil. This language — spoken by the people in his village of Saki and those of Lagos, Oyo, Ogun, and other Yoruba states in Nigeria — is part of the Niger-Congo group of dialects. My mother’s people are from Edo state in southwestern Nigeria. They are a people who can trace their lineage back thousands of years, a people that used to be called Igodomigodos, before being renamed the Edos by Oba (the Edo word for ‘King’) Eweka I. Their language, also called Edo, is of the Volta–Niger subgroup of languages also within the Niger-Congo family. Edo and Yoruba, two languages that should be as familiar to me as my name, yet they are not.

The eyes through which I see the world, my habits of thought, and the languages with which I dialogue with the world are an amalgamation of my parents’ ethnic and personal histories and a reality which mandated that English take precedence in our household. Though I was born in Port Harcourt, my family bounced around a lot during my childhood. Through all these geographic changes, the one constant was language; between my parents and their children, that language was English.

I spent much of my time in Port Harcourt, a city of thousands of ethnic groups and tens of thousands of expatriates. Two worlds collided in my home. In one, we were similar to an aristocratic British family where children were banished from the dining table for such atrocities as holding the fork in the right hand instead of the left or resting elbows on the dining table while eating, and good little girls, such as I was supposed to be, curtseyed or prostrated themselves when they greeted their elders. Good little children, such as I was instructed to be, only played with other good little children of similar or higher socioeconomic status. You said “yes, please” and “no thank you,” not because of an inviolable respect and reverence for others, but because “that’s how high-class people address each other.” You were admonished if you didn’t speak the Queen’s English. Beethoven, Michael Jackson, ABBA, and Madonna comprised the soundtrack of our lives, instead of King Sunny Adé, Brenda Fassie, Tshala Muana, or Fela Kuti. Absent from our library were any books about Pan-Africanist movements and liberation struggles. Bleaching creams were stacked on dressing tables as part of an ongoing battle waged against encroaching blackness, which also included staying out of the sun and doing all manners of things to rid ourselves of the natural kinks in our hair.

Ours was a world riddled with the persistent fear that our wealth invited the envy of all around us, and their envy brought with it untold threats and made others dangerous and unpredictable. Mother, the perpetual worrier and the one, being a woman, with the responsibility of maintaining our household, was also the steward of this wealth, her wary eyes always surveying our surroundings for danger. Any harm that befell us, the children, reflected badly on mother and spoiled her standing in the rigid social class strata in which we found ourselves.

“Don’t eat when we get to the Obbot’s house. Those bush people are so jealous of us they will poison us,” she would caution, with fire in her eyes.

“I don’t ever want to catch you playing with Idemudia. He’s below our class,” she warned about my close friend in primary school.

But it was never just Idemudia or the Obbots. It was also the Osas, the Ntuens, and many others, some of whom lived as comfortably as we did. All were suspect because in Nigeria “man must wack.” A person must survive at any cost.

![]()

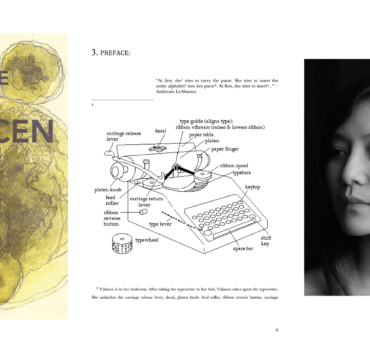

Omniglot.com tells me “Yoruba” is spelled like so: Yorùbá. From Genii Games’ Yoruba 101 app, I learn that the Yoruba Alufabẹẹti is comprised of twenty-five letters, though Omniglot disagrees, stating there’s a twenty-sixth. The alphabet contains letters familiar to English speakers and some that are not:

“G” (sounds like “ghee”) exists as does “Gb”, which is a difficult sound to describe phonetically. “O” and “Ọ”, with the former sounding like “oh” while the latter is pronounced like “uh”.

“S” is distinct from “Ṣ”, with the latter sounding like “shhh”.

Of all twenty-five (or twenty-six) my favorites by far are “gb” and “kp” because of how one has to say the first letter-sound in the hollow of your throat then roll that sound into the utterance of the second letter-sound.

“Gb” sounds like the echoing of a drumbeat, while “kp” sounds like reverberating cymbals.

When I run into Yoruba people on the streets of New York where I live or in the Nigerian restaurants dotting the city, they greet me in my language.

“Bawo ni?”

With great pride I utter the correct response memorized from the recent Yoruba language website I was poring over.

“Mo wa daadaa, o ̣se.”

Sometimes they ask me my name.

“Ki ni orukọ rẹ?” and I am ready with the apt response.

“Mi ni —.”

Wanting to know just what type of Yoruba I am, they ask where I’m from. “Nibo ni o ti wa?”

I stumble over my answer.

“Lati Oyo State,” is how I eventually respond even though Oyo State only speaks to half of my lineage. The other half, the maternal part is Edo, but Nigeria is a patrilineal society and I’ve grown used to saying Oyo first and Edo second, if I bring up the second at all.

For me, the inability to speak the language of my people represents the distance between the Nigeria I was taught to see and the one I want to see.

The Nigeria I was taught to see was one that was out to get us.

It was the world just beyond our tall cement fence, capped with sharp shards of green and brown glass. The Nigeria I’d love to see? One in which I maneuver the streets of Port Harcourt, Lagos, Ibadan, and other cities using the languages my ancestors inherited from my ancestors. One where I can say with the wisdom and instincts of someone enjoying the familiarity of home:

“You know that marketplace by…?”

Or

“I remember that bookstore next to the…”

Or

“I miss that buka on that street where we used to…”

The Nigeria I was taught to see was one of oil, of “how much” and “dash.”

Father was the Managing Director of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation — the largest oil corporation in Nigeria at the time — in Port Harcourt. Mom owned many entrepreneurial ventures, like her Hotel Mona Lisa, one in Port Harcourt and another in Warri, both catering to the German, Lebanese, British, French, American oil expats and aspiring ogas. In contrast to our relatives visiting from the village or the so-called family friends whom mom regarded with suspicious looks, these expats were treated to our suya and our stout, and allowed to sit on the plush green sofa in our second living room — the one reserved for “distinguished” guests, people like Chief Fawehinmi, who, every time he arrived in his gleaming black Benz, clad in a flowing brocade agbada, was accompanied by a fair-haired European, an air of entitlement wafting in with them.

Afterwards, the guests would scurry away in the aftermath of a brokered business deal. Mom and dad would retreat into their haven where the second world in our household commenced. Here, the lingua franca was not English. Here dad’s Yoruba met mom’s Edo, their mingling sounds a symphony of heavy consonants and long vowels. On a bad day, which was most days of their marriage, these sounds clashed and rang through our household. They fought in these languages. They shared secrets through them and locked us out of their esoteric world.

As a child, I never questioned the predominance of English in our home. After all, the same values were reflected in every aspect of Nigerian society including schools, media, government, film, literature, workplaces, and in everyday interactions with strangers on the streets, market places, offices, and so on. The languages we were taught in school were typically French (or Latin in father’s time), not even Edo or Igbo or Hausa or Ibibio or Yoruba or any one of the more than five hundred languages my people speak. Because of this nationwide complicity in the denial and relinquishing of our mother tongues, I can’t blame my parents for their choices.

Father had the backbreaking pressures of being the first member of his family to go to school.

“To get there I had to travel very far. Sometimes I had to swim there,” was the story he’d often tell. “But my father wanted me to go. He wanted a better life for me and he wanted me to make a better life possible for the rest of the family, which is why I didn’t have to work on the farm like my brothers and sisters did.”

With the benefit of an academic scholarship, he left Nigeria in the 1960s, swapping a newly independent country on the verge of a civil war for its colonial master, Britain. In black and white pictures of him prior to his emigration, father’s slanted tribal marks shone, his cheeks and chin were always clean-shaven, and a shy smile lifted the corners of his lips. The pictures he later took in Birmingham showed a sullen man, his beard covering up those marks that linked him with his people. His small awkward smile only ever appeared in photographs when we were also with him.

Even after returning to Nigeria in the 1970s and ascending the ladder of oil-fueled success, he never shaved his beard again, never revealed the patterns his father, a Sango Priest, had etched into his cheeks and packed full of herbs while chanting prayers for his success.

“You don’t know how good you have it,” mom always said to us.

She’d regale us with stories about being poor, about the father that stood in the way of her education, about traveling far from home to somewhere in Igboland to serve as a housegirl for another family. She made it to the UK somehow — we were never told how — only to be looked down upon by the whites there, only to experience the type of poverty that forced her to eat canned cat food because it was all she could afford. By the time she met my dad at a student dance in Birmingham, rage had hardened her.

“You have to be better than them, always,” she’d say to us in the rare moments when she wasn’t screaming at us or beating us.

“Them” meaning white people.

“Better than” meaning mastering things like English at the expense of our own languages.

It was in search of the better-than life that my mother brought me to America in 1991. I spent a portion of my first year in a strict Christian high-school in High Point, North Carolina. There were white students everywhere. The principal mistook my Nigerian accent for a symptom of deficient mental capacity and decided to hold me back a year, so into the tenth grade I went. It was on the day we started reading Hamlet when I discovered that those white kids had a mangled grasp of the English language, that Africans were being forced to place a higher premium on the language than these people whose lips were fashioned to utter it in the first damn place.

“What does it mean, Ms. Eubanks?” the students cried out, befuddled to the point of frustration, biting their tongues and cheeks in vain attempts to read the dialogue aloud.With a smirk on my face, I showed them how. The only foreigner in that all-white class and I was more adept at the language than they were. But inevitably, every day after school I came home to a mom who roared into the phone in Edo or Yoruba, her words colliding one into another at rapid pace and not one of them meaning anything to me.

I can recognize this concerto of hard and soft tones anywhere. I’ve heard it float above the din of noise on Harlem’s 125th street in the height of summer and the force of recognition has stopped me mid-stride. I’ve heard it behind me at the vegetable aisle of the grocery store and whirled around to find a full-bellied, head-tied, round-faced, cocoa-brown woman picking her way through a pyramid of navel oranges, chattering away, regaling the person on the other side of the phone with stories in Yoruba. The gb, kp, and eh sounds, even though I don’t always know what the words they form mean, as familiar to me as air.

After twenty-four years in the U.S., I realize my parents were right: speaking English fluently is the cultural capital that, in a lot of ways, has made my economic survival possible. When I was undocumented, it meant I could pass as an American and, especially in the years after 9/11, made finding employment possible. Speaking English fluently gained me access to middle- and upper- middle class circles, and helped me navigate the interlocking worlds of academic, leftist, activist, and white spaces with relative ease.

Yet my parents were also very wrong: not knowing my languages is erasure, a symptom and manifestation of white supremacy. It is a continuation of the pillaging the British began in my homeland many years ago, when they named it Nigeria and attempted to subjugate the people, eradicate our cultures, and invisibilize our histories. As much as I possess a mix of English register and language that enables access into various spaces, I long for Yoruba and Edo, the familial ways of speaking for which I lack the words.

Today I am an embodiment of myriad tongues.

In my everyday life, I speak the English the Brits brought to Nigeria, the English of the African immigrant on U.S. soil that alternates between rolling Rs and hard Ts (‘water’ versus ‘warra’), the pidgin English that is a marriage between our native tongues, urban slang and a deconstructed English, and the little bit of Yoruba and Edo I’m picking up from websites and apps. How I employ these languages of course depends on the setting.

With my Naija friends, with whom I’m usually more at ease, pidgin flows out of me unhindered:

“How body?”

“Body dey inside cloth.” “You dey see am?”

“I dey see but I no ‘gree. Story don get k-leg, abi?” “I no know wetin do am O. Mumu” [sucks teeth]

Speaking with co-workers — who, given the relatively few African immigrants in the U.S. nonprofit world, are usually not African — my language is American English all the way. This never feels completely comfortable. Yet I’ve had over two decades of practice:

“Hey there! How’s it going?” “I’m doing alright.”

“Did you see that post last night?”

“Yep! And I disagree completely. The author doesn’t know what they’re talking about.”

Speaking with my best friend means we blend Urban English, and three different types of patois

— Hawaiian, Japanese and Nigerian — creating a whole new dialect in the process:

“‘Sup”

“Not much.”

“Aiyah! Can you believe that shit? I read it and I just wanted to maka.”

“Wahala. I dunno wetin dat person was thinking posting such ridiculousness. Onuku!”

With a rich donor — whose generosity is the life-blood of the nonprofit I work for — the formal politeness and aristocratic good manners my mama taught me informs my speech:

“Good to see you again!”

“You as well. How have you been?”

“I have been well. Thank you for asking!”

“I have been meaning to check in with you about the confusing post I read on my feed last night.” “Yes, Mr. —, I am so glad you brought that up. Please rest assured, it is completely inaccurate and we are dealing with it.”

“Oh what a relief!”

In the years since my interaction with the man at Festac Grill, I’ve been teaching myself my languages gradually. What I do know is how easily the words roll off my tongue, how deeply soothing it is to pronounce them:

Ẹ ku abọ Vbèè óye hé? Ẹ ku aarọ

O ye mi

Kpẹlẹ

Koyo

I say these words to dig deeper into who I am, a child of the red soil of Benin, the grey mountains of Saki, and the ocean city of Port Harcourt. These Edo-Yoruba words ground my shaky identification with the country into which I was born yet still barely know. They allow me to picture a different life for myself, one in which we kids were granted access into our parents’ polyglot world, and where at night I dream in Edo and during the day — one day — I write in Yoruba.

Image Credits: Ian

Ola Osifo Osaze is a trans masculine queer of Edo and Yoruba descent, who was born in Port Harcourt, Delta State and now resides in Houston, Texas. Ola has been a community activist for many years including co-founding the Black LGBTQ+ Migrant Project, working with Transgender Law Center in Oakland, the Audre Lorde Project, Uhuru Wazobia, Queers for Economic Justice and Sylvia Rivera Law Project. Ola is a 2015 Voices of Our Nation Arts workshop (VONA) fellow, and has writings published in Saraba Magazine, Apogee, Qzine, Black Looks and the anthologies Queer African Reader and Queer Africa II. Ola writes to visibilize the myriad journeys and resiliency of queer/trans African migrants, particularly those straddling the worlds of West Africa and North America, and is working on a short story collection that does just that. You learn more about Ola's activism here - https://transgenderlawcenter.org/programs/blmp.