I

have often pictured her at a kitchen table, the newspaper at an angle, the ink of the newsprint on her fingers. In her left hand, a cup of warm tea. At the window, Rose of Sharon.

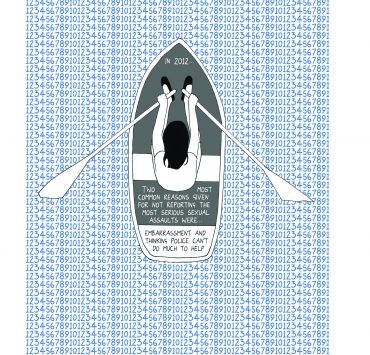

This began in college. I was reading for the first time about the Dirty War in Argentina and found it impossible to believe that although many people had protested, many more women and men had lived through that time and done nothing. They had drunk mate and tended to flowering shrubs, and meanwhile all around them, underground and way above ground, the military boots, the screams, the gagging, the testicles and nipples electrocuted, the skin peeled from the soles of the feet with hot nails, and the murders. Always the murders.

I shivered, reading about the disappearances and the mass killings, but it was the woman I wondered about. The one in her kitchen. The one chopping yellow onions for dinner. The one who heard the neighbors and did nothing.

I had been thinking about her since high school when once a year slavery would become a page or two in a textbook marked with wide titles like A Complete History of the United States. The teacher wanted us to focus on the white Southerners, but I kept thinking about the woman (surely there were many women) who sat in the kitchen, the ink of the newsprint on her fingers and did nothing.

Once, sitting on the F train, I thought of her. I don’t know why. I must have been reading a magazine piece that mentioned slavery. Or I was having one of those moments that only ever happens in New York City when you glance around the subway car and you see so many countries all at once and so much of the past and what the future will be and it makes you hold your breath and think: How? How did we ever agree to enslave people? To murder?

She was connected always with the word “how.” The woman in the kitchen. She was that question. How. How. How.

Now I know.

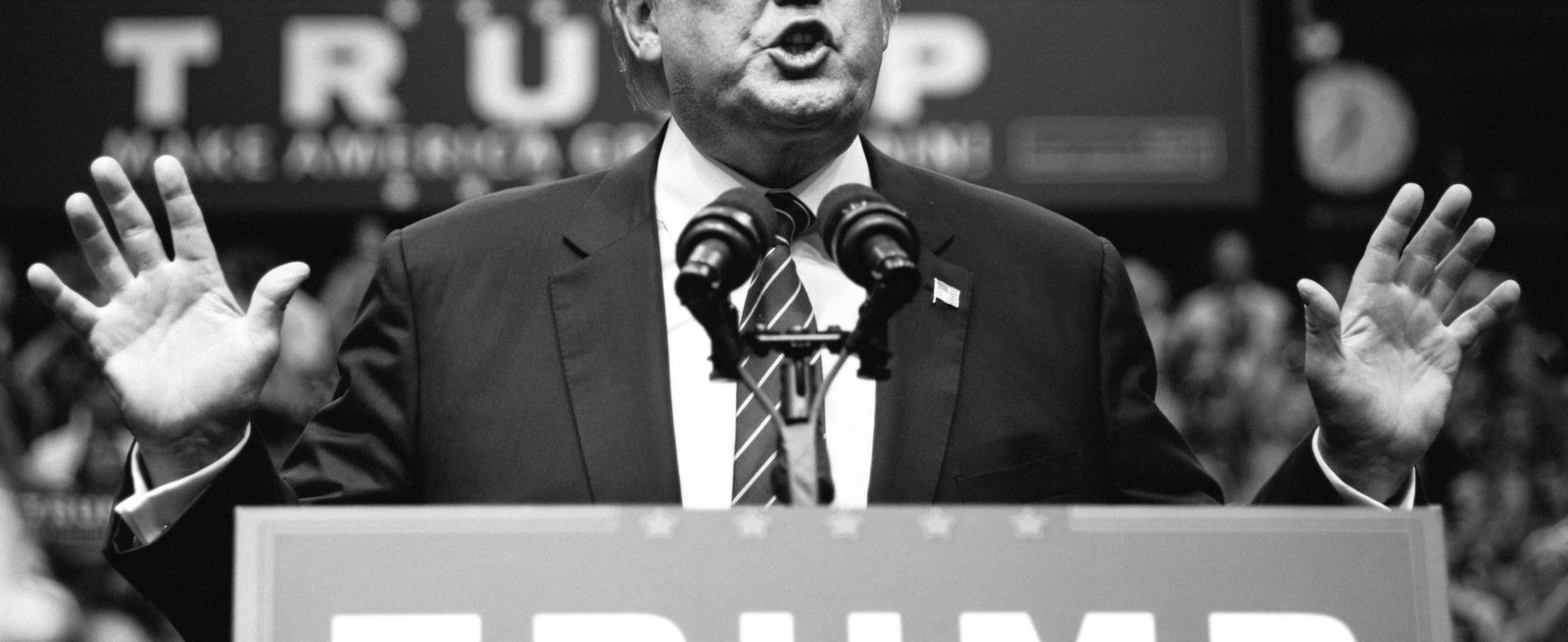

She is in the kitchen, slicing cilantro, jalapeño, ginger. The neighbor trudges up the staircase. The laptop live streams the political rally of the evening. The front runner. He waltzes on stage. He’s bragging again. He has started a foundation for soldiers and donated millions. He called his friends. They gave a hundred thousand. A million dollars. No questions asked. He can do that kind of thing. He is the front runner. The crowd cheers. Women and men, all of them faceless, the back of their heads fill the lowest part of the TV camera.

The cilantro sticks to her fingers. She believes they don’t understand. If only they would understand. But they do. They have made him the front runner.

At the kitchen table, she reads in a newsmagazine about the interview where he was asked if he meant it when he said he would murder the families? Would he actually kill women and children? The children whose fathers were terrorists? His answer: “I would do pretty severe stuff.”

She reads about the women and the men. How when they heard the front runner commit to murdering women and children, one man screamed, “Yeah, baby!” and the women applauded. The men too.

In the kitchen, she remembers Audre’s words: “I am myself—a Black woman warrior poet doing my work—come to ask you, are you doing yours?”

She does not have newspaper ink on her fingers. She thinks: This is how it happens. She knows now. Chopping the cilantro, washing the spinach, the whole country in third person, she and he and they, not I. Not I.

Daisy Hernández is the author of The Kissing Bug: A True Story of a Family, an Insect, and a Nation’s Neglect of a Deadly Disease, which won the 2022 PEN /Jean Stein Book Award and was selected as an inaugural title for the National Book Foundation’s Science + Literature Program. She is also the author of the award-winning memoir A Cup of Water Under My Bed and coeditor of Colonize This! Young Women of Color on Today's Feminism. She is an Associate Professor at Northwestern University.