In honor of our own Las Cuerpas, Aster(ix) is going graphic. Here are our picks right in time for the holiday season.

Palestine by Joe Sacco (journalism/reportage)

Palestine by Joe Sacco (journalism/reportage)

“Based on his research, interviews, and personal experiences in Palastinian Occupied Territories in 1991 and 92, [Palestine] takes you there and gives you a first-hand account of the atrocities and suffering in the conflict with Israel. He gives you a close up visual rendering of the physical and emotional conditions of the people, who struggle daily for survival… Sacco has rendered the terrible conditions of life into a compelling and sympathetic artistic documentary. It is sad, but most good stories are sad… What’s better, his drawing is detailed and realistic, very approachable and interesting.”

—American in Auckland

Asterios Polyp by David Mazucchelli (fiction)

Asterios Polyp by David Mazucchelli (fiction)

“David Mazzucchelli’s boldly ambitious, boundary-pushing graphic novel is remarkable for the way it synthesizes word and image to craft a new kind of storytelling, and for how it makes that synthesis seem so intuitive as to render it invisible…Asterios Polyp is a fast, fun read, but it’s also a work that has been carefully wrought to take optimum advantage of comics’ hybrid nature — it’s a tale that could only be told on the knife-edge where text and art come seamlessly together.”

–NPR’s The Five Best Books to Share with Your Friends

City of Glass: The Graphic Novel by Paul Karasik, David Mazzucchelli, Paul Auster, and Art Spiegelman (fiction)

City of Glass: The Graphic Novel by Paul Karasik, David Mazzucchelli, Paul Auster, and Art Spiegelman (fiction)

A comic of City of Glass? But why? The idea sounds bizarre, even repellent: could there be any possible justification for turning a great novel into a graphic novel? Originally published in 1985, City of Glass was the first part of Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy, and instantly made him famous. Confining himself to fewer than 150 pages, Auster wrote a fascinating meditation on identity and fiction, structured within a very literary detective story. Daniel Quinn, once a promising poet, now writes crime novels under a pseudonym; he receives a phone call intended for a detective named Paul Auster, and accepts an assignment to shadow Paul Stillman, a bookish lunatic. Quinn pursues Stillman, meets a writer named Paul Auster, loses himself on the streets of New York and disappears into madness. You can understand why someone might want to make City of Glass into a movie, or a play, or even, perhaps, a series of paintings. But why turn a book into another book? Why make a novel from a novel?

This new edition – published in the US in 1995, the comic has taken a decade to cross the Atlantic – comes with an introduction by Art Spiegelman, who offers a few possible answers. First, why not? Second, because it seemed difficult, and therefore interesting. Third, as a spokesman for comics, Spiegelman wanted to secure some highbrow credentials for the form, and had the neat idea of commissioning novelists to write texts for artists to illustrate. He approached Auster, who declined to write a new text, but suggested using something he had already published. Spiegelman offered the job to David Mazzucchelli, fresh from working with Frank Miller on Batman: Year On. When Mazzucchelli got stuck, Spiegelman brought in Paul Karasik. Eventually, the comic became a collaboration between the two artists: Karasik and Mazzucchelli worked on alternate drafts, sending their drawings back and forth, each working over what the other had done…

—The Guardian

Building Stories by Chris Ware (fiction)

Building Stories by Chris Ware (fiction)

Ware has been consistently pushing the boundaries for what the comics format can look like and accomplish as a storytelling medium. Here he does away with the book format—a thing between two covers that has a story that begins and ends—entirely in favor of a huge box containing 14 differently sized, formatted, and bound pieces: books, pamphlets, broadsheets, scraps, and even a unfoldable board that would be at home in a Monopoly box. The pieces, some previously published in various places and others new for this set, swarm around a Chicago three-flat occupied by an elderly landlady, a spiteful married couple, and a lonely amputee (there’s also a bee bumbling around in a rare display of levity). The emotional tenor remains as soul-crushing and painfully insightful as any of Ware’s work, but it’s really insufficient to talk about what happens in anything he does. It’s all about the grind and folly of everyday life but presented in an exhilarating fashion, each composition an obsessively perfect alignment of line, shape, color, and perspective. More than anything, though, this graphic novel (if it can even be called that) mimics the kaleidoscopic nature of memory itself—fleeting, contradictory, anchored to a few significant moments, and a heavier burden by the day. In terms of pure artistic innovation, Ware is in a stratosphere all his own.

— Booklist

Marzi by Marzena Sowa and Sylvian Savoia (memoir)

Marzi by Marzena Sowa and Sylvian Savoia (memoir)

Marzena Sowa’s memoirs of growing up during the fall of communism in Poland demand to be told in the graphic novel genre. Her experiences, emotions, and memories transcend words. While much of Sowa’s childhood provides opportunities for readers to connect with her, there is so much more that takes us to a place and time that many of us don’t…and hopefully will never…know. In her new graphic novel, Marzi, Sowa does a magical job of weaving the two together–the familiar and the unfamiliar–to create an uplifting narrative that is a delight to read…and to look at.

—Patheos

The Complete Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi (memoir)

The Complete Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi (memoir)

A memoir of growing up as a girl in revolutionary Iran, Persepolis provides a unique glimpse into a nearly unknown and unreachable way of life… That Satrapi chose to tell her remarkable story as a gorgeous comic book makes it totally unique and indispensable.

—Time

Epileptic by David B (memoir)

Epileptic by David B (memoir)

The French cartoonist David B.’s extraordinaryL’Ascension du Haut-Mal, just published in its entirety in English for the first time as Epileptic, supersedes the standard line, exactly as the best art is supposed to. It’s neither cinematic nor literary: At every turn, it does things that only comics can do. It is entirely, obsessively, mesmerizingly the work of a single visual artist, and its narrative is the devastating story of how his vision rose from sickness and despair.

—New York Magazine

Habibi by Craig Thompson (fiction)

Habibi by Craig Thompson (fiction)

Craig Thompson’s new graphic novel, Habibi, is a masterpiece. This isn’t an opinion. This book is a gorgeous object; to make it, Thompson apparently covered himself in honey and rolled around in a thousand years of Arabic calligraphy and Islamic art, and the result is breathtaking.

—The Boston Phoenix

Logicomix: An Epic Search for Truth by Apostolos Doxiadis, Christos H. Papadimitriou, Alecos Papadatos, and Annie Di Donna (biography/fiction)

Logicomix: An Epic Search for Truth by Apostolos Doxiadis, Christos H. Papadimitriou, Alecos Papadatos, and Annie Di Donna (biography/fiction)

This exceptional graphic novel recounts the spiritual odyssey of philosopher Bertrand Russell. In his agonized search for absolute truth, Russell crosses paths with legendary thinkers like Gottlob Frege, David Hilbert, and Kurt Gödel, and finds a passionate student in the great Ludwig Wittgenstein. But his most ambitious goal–to establish unshakable logical foundations of mathematics–continues to loom before him. Through love and hate, peace and war, Russell persists in the dogged mission that threatens to claim both his career and his personal happiness, finally driving him to the brink of insanity.

–Amazon

A Drifting Life by Yoshihiro Tatsumi (autobiography/origins of manga)

A Drifting Life by Yoshihiro Tatsumi (autobiography/origins of manga)

It’s a book that manages to be, all at once, an insider’s history of manga, a mordant cultural tour of post-Hiroshima Japan and a scrappy portrait of a struggling artist. It’s a big, fat, greasy tub of salty popcorn for anyone interested (as Americans increasingly are) in the theory and practice of Japanese comics. It’s among this genre’s signal achievements.

—New York Times

Hip Hop Family Tree by Ed Piskor (biography/history/ethnomusicology)

Hip Hop Family Tree by Ed Piskor (biography/history/ethnomusicology)

Cartoonist Ed Piskor’s latest book collects his non-fiction comic strip history of Hip Hop… Piskor has a special knack for creating comics that appeal to audiences beyond those of us who frequent comic book shops and bookmark webcomics for daily reading.

–BoingBoing

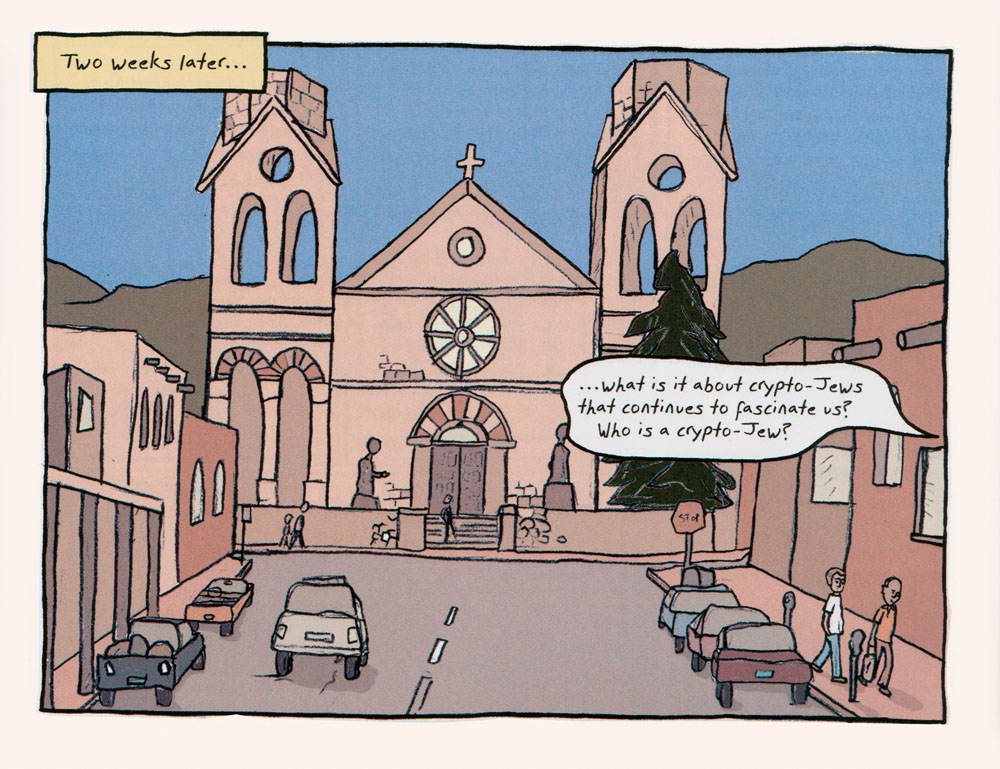

El Iluminado by Ilan Stavans (fiction)

El Iluminado by Ilan Stavans (fiction)

Ilan Stavans and Steve Sheinkin’s graphic novel takes a highly entertaining and informative journey through a largely unknown slice of New Mexican and Jewish history…. El Iluminado reads a bit like a crypto-Jewish DaVinci Code…. An undeniably weighty and meaningful chapter of American history, an epic tale with a tragic sweep…. A reminder of the human longing that often drives those who search for their ‘true’ religious and cultural identities.

—Los Angeles Times, Jacket Copy

Marble Season by Gilbert Hernandez (semi-autobiography)

Marble Season by Gilbert Hernandez (semi-autobiography)

Set in a lower-middle-class multiracial Southwestern suburb in the early 1960s, Marble Season is a wonderfully evocative account of a group of kids for whom popular culture… serve as both a lingua franca and a not wholly reliable guide to the mysteries of social life…in Marble Season, the slow encroachment of adolescence, both a threat and a promise, gives the work emotional heft.

–The Globe & Mail

My Dirty Dumb Eyes by Lisa Hanawalt (mixed genre)

My Dirty Dumb Eyes by Lisa Hanawalt (mixed genre)

My Dirty Dumb Eyes is a zero-attention-span assemblage of surreal one-page drawings, clusters of gag cartoons (“How We Can Tell Martha Stewart’s Drunk”), short comics stories, illustrated movie reviews and garish stoner tableaus. They add up to a wildly entertaining portfolio from an artist with a masterly painting and drawing hand, obsessions with animals and genitals, and a very weird, intentionally dopey sense of humor.

—New York Times

The Man Who Laughs by David Hine, Victor Hugo, Mark Stafford (fiction)

The Man Who Laughs by David Hine, Victor Hugo, Mark Stafford (fiction)

Better known for its legacy than anything between its pages, Victor Hugo’s ghoulish fable The Man Who Laughs inspired the silver screen classic that inspired the demented rictus of the most iconic comic-book villain of all time.

Fittingly, then, this adaptation – edited for pace and impact from the somewhat leaden pace of the original prose – comes from the prolific David Hine (Strange Embrace, Spawn), who homaged the novel in a 2011 issue of Batman And Robin.

–SciFiNow